12/11/2008

A Brief Tour of Norwich Castle Museum

by visiting Ecology Students from Easton College

The tour was conducted by Dr Tony Irwin, Curator of Natural History.

Of the natural history collection, the bulk is not on display. Only 10% of the birds are displayed, and 1% of the invertebrates. The rest are stored in the building which was formerly the county court, and may be seen by appointment only. The art and archaeology collections also store most of their collections there.

The natural history collection started here in the 1820s when Sir James Edward Smith (December 2, 1759 - March 17, 1828) a botanist and founder of the Linnean Society, brought his entire collevction to Norwich in 1796. He had bought it from Linnaeus son, before the Swedes were aware it was for sale. The Literary Institution Smith formed with his friends hired rooms to house their collections of books.

The Institution had premises in the house of Simon Wilkin, a local printer, in Haymarket, Norwich. In 1825 the Norfolk and Norwich Museum opened there, with George Denny the first curator.

In 1834 the museum was in Exchange Street, and open to members of the Institution.

In 1838 the museum moved again to St. Andrew's Street. Its displayed natural history collections with some archaeology and ethnography.

From 1840 the public were regularly allowed in free. In the nineteenth century museums were seen as a means of education and "civilising" people.

In 1883 a new prison was started on Mousehold Heath. The City acquired the Castle and old prison.

John Gurney (1845 - 87) of Sprowston suggested that the Castle should be used as a museum and paid œ5,000 towards the cost.

In April 1883 the private collections of the Norfolk and Norwich Museum were given to the City of Norwich and Norwich Castle Museum opened in October 189.

Nowadays donations are still the main means by which the collections grow, storage and display are expensive and must represent good value.

A recent example is of "voucher" specimens of insects bbeing donated from a collector in North Norfolk. Voucher specimens are duplicates which help identify specimens and help in making taxonomic decisions.

The curators are often asked why they need so many "spare" specimens - one answer is that predation and decay need to be countered, these are major factors in the storage strategy.

If donations are to be of value, they need to be very well documented, although DNA can provide information it

is not usually enough.

Tony told us of a Bramble collection which they have recently acquired, which is not well documented, but which they will keep somewhere until is becomes useful. It is a "time machine" from the mid 19th Century.

Some items from collections when acquired are redistributed, such as a Capercaillie which was of such quality it was sent up to Perth, who already had several.

The paintings on the landings were by Nick Arbor - a reconstruction of an interglacial landscape in lowland Britain. Typical mammalian fauna as shown depict brown bear, spotted hyena, boar, elk and giant and red deer.

Discussion of a new display of the West Runton Mammoth ensued, and Crag

deposits - beds of shells, teeth of small rodents, stranded whales, bloated

floating elephants and generally mixed bits!

The bird skeletons, a Vulture and a Pelican, were amongst the many items from John Henry Gurney Senior.

The bird skeletons, a Vulture and a Pelican, were amongst the many items from John Henry Gurney Senior.

Norwich had the best bird of prey collection in the world in the late 19th Century.

It was sold to the Natural History Museum by R. Rainbird Clarke the anthropologist - 10,000 birds!

We visited a workshop where rubber casts were being used to model fossil shark teeth and urchins.

The freezers here were stocked with bodies as received - such as a barn owl in a platic bag. They are examined for other creatures, lice and mites, as well as being used for research themselves.

Locally trawled wood from the North Sea bed had been received, but with little background information - it is kept wet before being examined. It represents ancient forest.

Low quality stuffed creatures with no provenance are often given to schools or simple thrown away, such as this Heron.

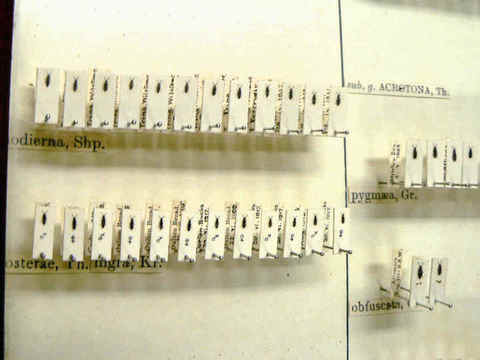

We were shown a collection of Bedwell's many Rove Beetles, Staphylinidae, collected between 1890 and 1940. Some were collected by exchange with other collectors. They are laid out taxonomically and original notebooks are kept, but as swaps occurred, the notes are not always relevant to the specimens.

Beetles are rarely well known species - for example even the Stag Beetle is usually misidentified, in Norfolk only the Lesser Stag Beetle is normally found.

We saw drawers containing Type specimens from JB Bridgeman around 1895 -

parasitic wasps. They were distinguished in the drawers by mounting against

red card alongside other voucher specimens. The holotype is the defining example

which is used to describe a species, together with the often inadequate verbal

description, eg "black with red legs"! If no holotype was defined a lectotype

is selected from the specimens later.

These specimens are photographed at multiple focal lengths and positions to

create merged images which attempt to digitally represent the creature and

avoid the need to send rare and delicate specimens by post.

An example of the endangered Kakapo was shown - less than 100 in the wild on 4 small islands near New Zealand. A flightless parrot, it has no defence against introduced predators - stoat, cat and rat - as it can only climb trees and glide. Their behaviour, lekking, and their calls also make them vulnerable.

Kiwi in bubble wrap

Cassowary and baby Ostrich specimens being kept ready for a future display.

These specimens are stored in a freezer to kill infesting parasites.

These specimens are stored in a freezer to kill infesting parasites.

Specimens are protected from the Museum Beetle Anthrenus verbasci, related to Carpet Beetle, by sealing specimens in polythene bags.

They can enter the bag, but cannot get out to spread further.

These birds are "study skins", legs, wings and skulls being the only bones

left in. They can be studied to some extent without removing the bag, so

avoiding contamination.

Other birds are stuffed and mounted. They have fridge magnets on their bases and the storage trays have metal sheets to which they stick and so avoid disastrous domino effects when opening drawers!

The Blackbird collection has few normally coloured specimens because the albinos are more interesting to collectors.

Often quite common species are scarce in collections because of their low interest to the general collecting public, and because they are protected. This is particularly true of some amphibians, which are pickled, not stuffed, and they represent gaps in museum collections.

Egg collection being illegal means that data on recent trends in egg strength and thickness is hard to obtain.

Illegal collections rarley have provenance and so have little scientific value.

There is a library of stored supplementary documents - books, logbooks, diaries, notes - which often comme with a donated specimen collection.

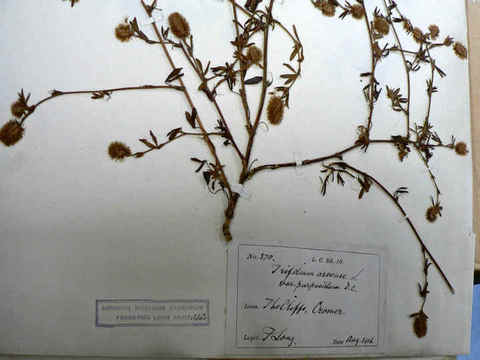

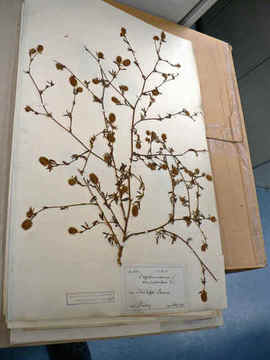

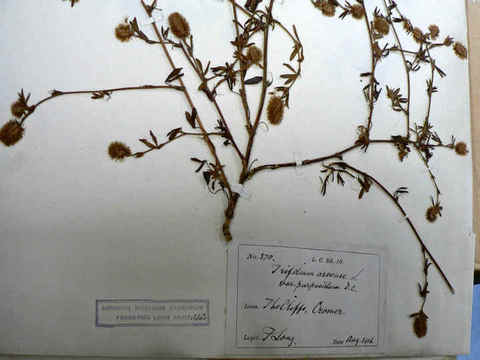

The herbarium pressed plants are voucher specimens and are entered and double checked.

Trifolium arvense, Rabbits Foot Clover, from 1916.

Small samples may be taken from pressed collected water plants and analysed

for presence of diatoms, thus giving an insight into water quality of a

habitat. A temporal series represents the water history of a site, such as

Hickling Broad.

Lichen specimens in paper envelopes from all around the world are collected,

eg from Finland in 1927. Their chemistry is such that they respond by changing

colour like an indicator, when particular reagents are used with particular

species. All the data is entered into a database, and checked. This will then

be made available online, and feedback from experts will help establish the

databank.

We were shown Papilio spp. in the Fountaine-Neimy Collection of 23000 butterflies.

They were mainly bred or collected by Margaret Elizabeth Fountaine (1862-1940), a much travelled Norwich woman.

The males are not varied but the females are, and mimic a Danaid species, like the Monarch, which avoid predation by feeding as caterpillars on toxic Milkweed glycosides.

It is said that even when the Danaid species is not in the same range, this mimicry still occurs.

Fountaine kept a diary all her life and was also a prolific painter, she

painted the caterpillars of the butterflies she bred, as a record.

See the Museum website

The hat rack in the office!

Jim Froud

The bird skeletons, a Vulture and a Pelican, were amongst the many items from John Henry Gurney Senior.

The bird skeletons, a Vulture and a Pelican, were amongst the many items from John Henry Gurney Senior.

These specimens are stored in a freezer to kill infesting parasites.

These specimens are stored in a freezer to kill infesting parasites.