CHATEAUX OF THE LOIRE VALLEY.

| Page | |

| Introduction | 4 |

| Chateaux Fort | 6 |

| Chateaux of the Transition | 21 |

| Chateaux de Plaisance | 26 |

| Architects and Master Masons | 45 |

| Conclusion | 46 |

| Bibliography | 47 |

| PDF version | 14.58 MB |

Illustrations.

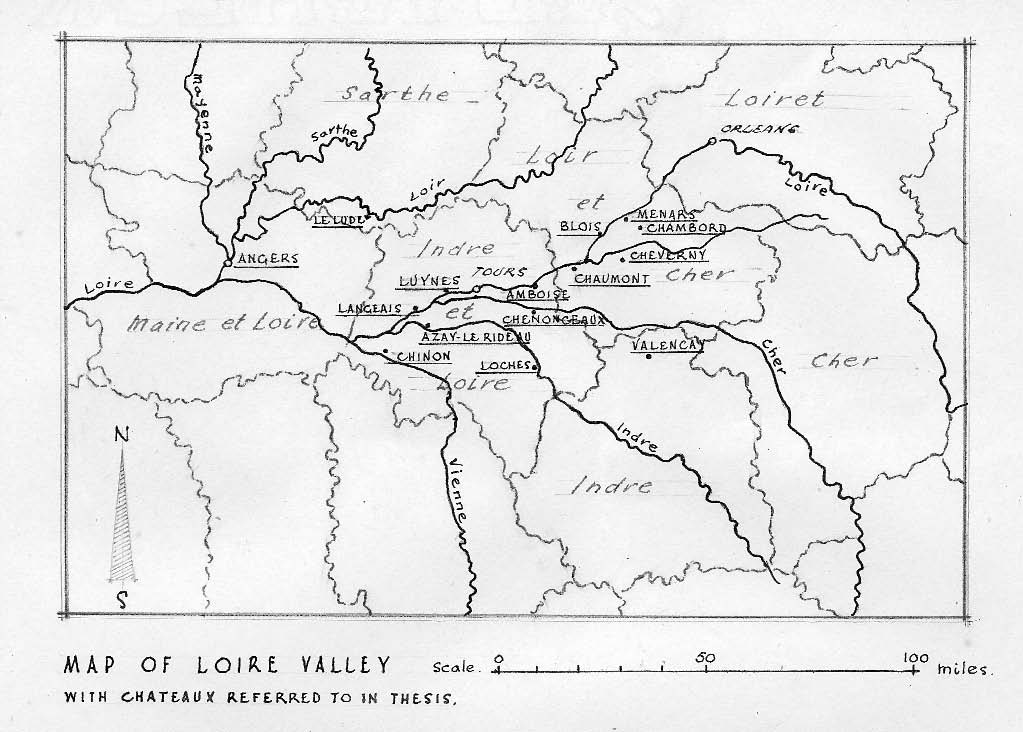

| Map of the Loire Valley | 4 | |

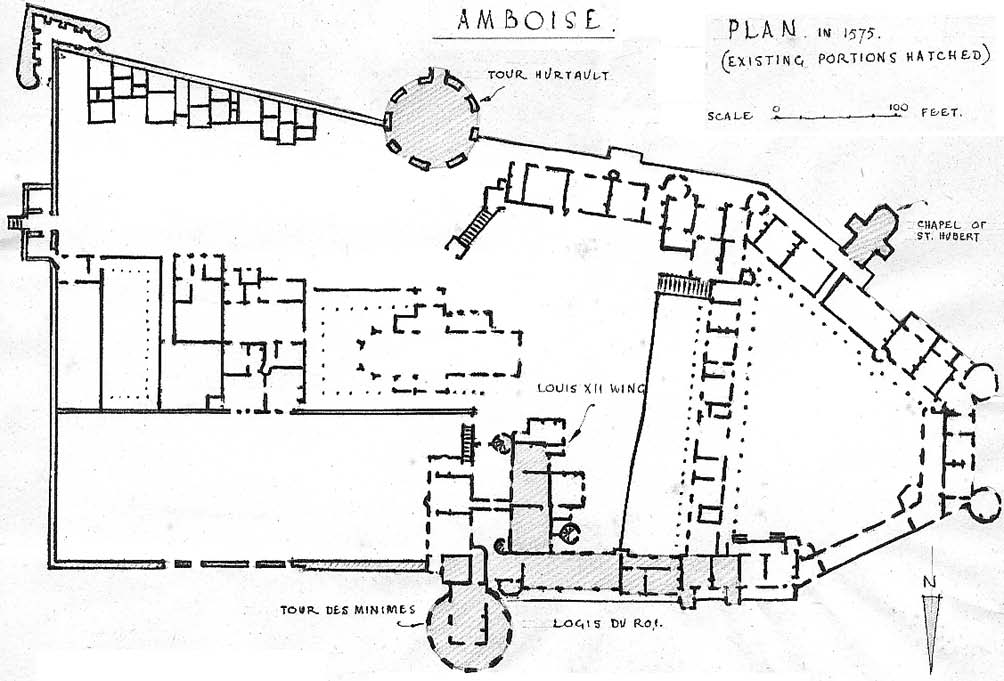

| Amboise | - Plan | 22 |

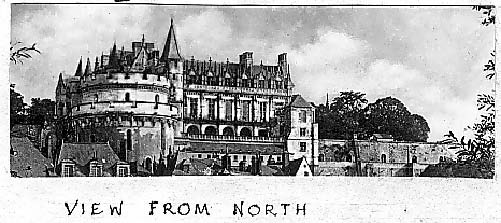

| - View from North | 24 | |

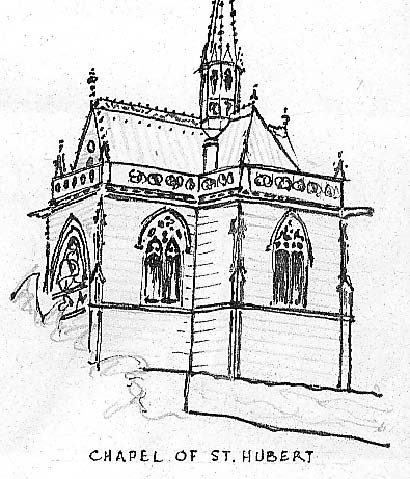

| - Chapel St. Hubert | 25 | |

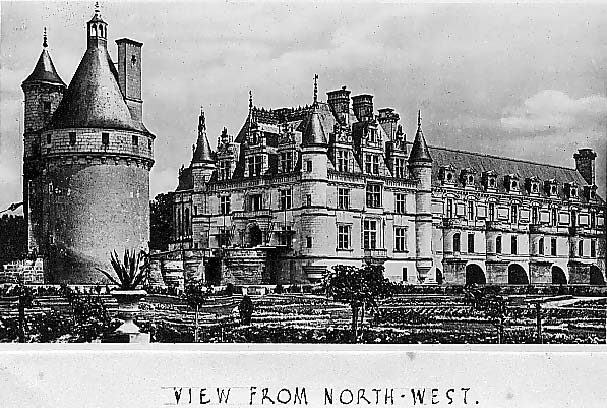

| - Diane de Poitiers Bridge, NW | 26 | |

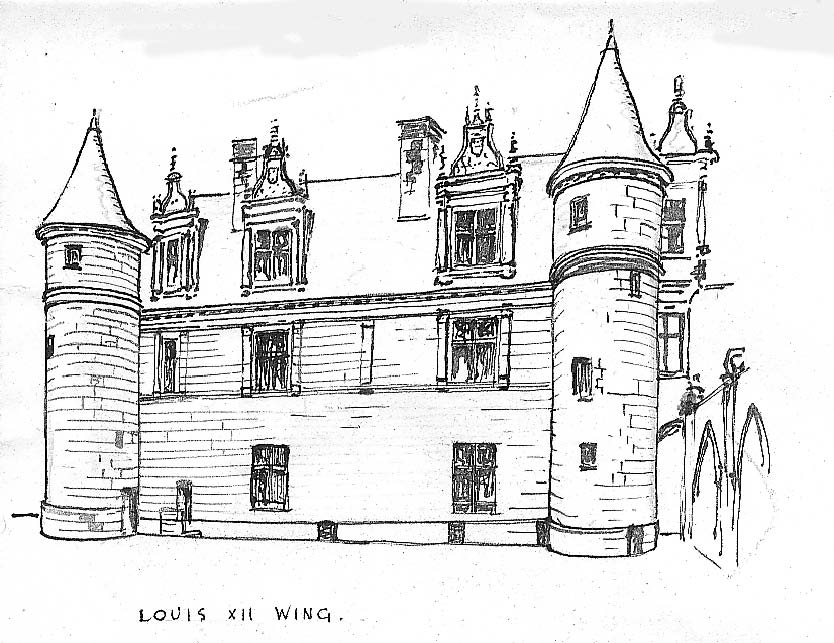

| - Louis XII wing | 22 | |

| - Neo-classic details | 27 | |

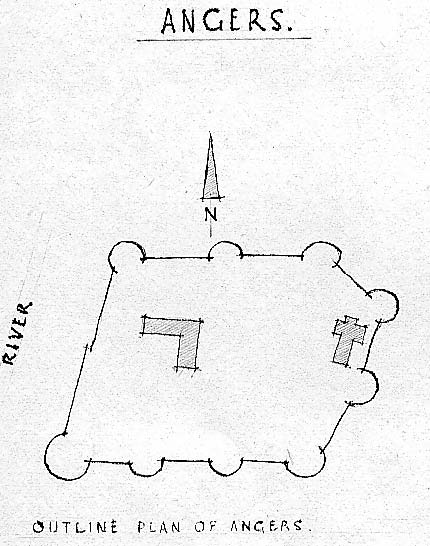

| Angers | - Plan | 8 |

| - towers | 9 | |

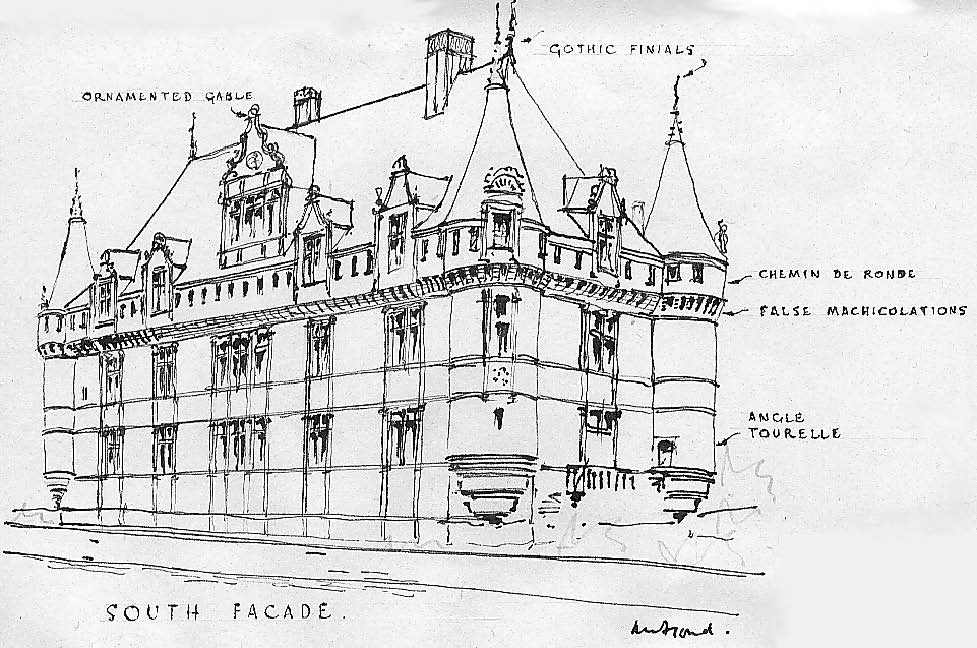

| Azay le Rideau | - South facing view, Plan | 28 |

| - Bastion | 29 | |

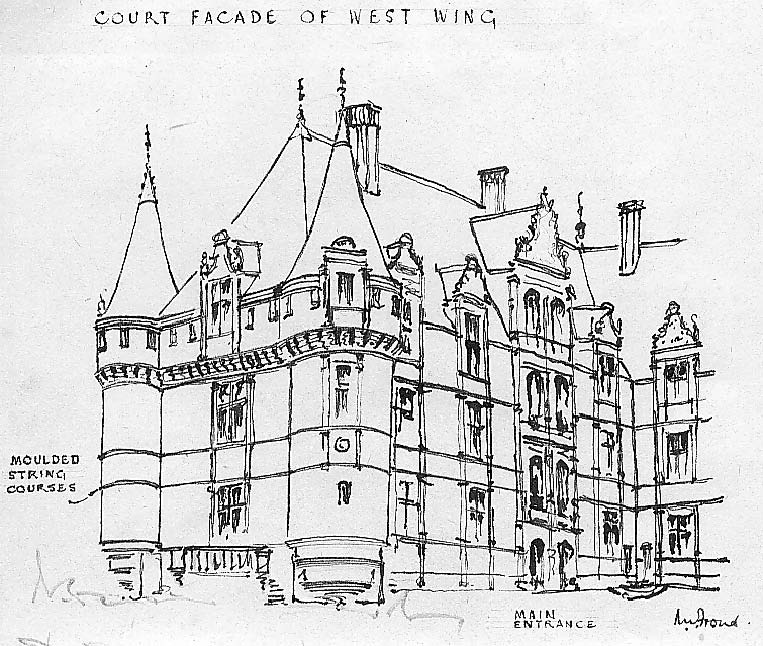

| - West wing with moulded string | 30 | |

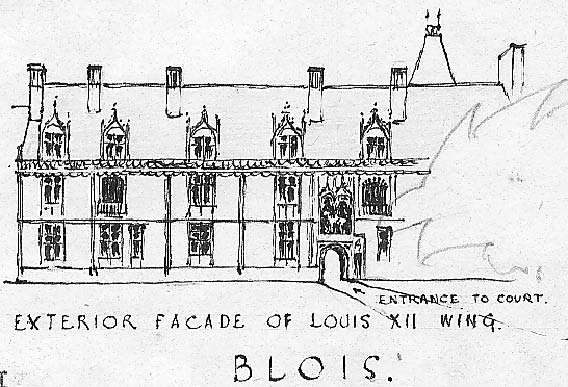

| Blois | - Entrance to court | 11 |

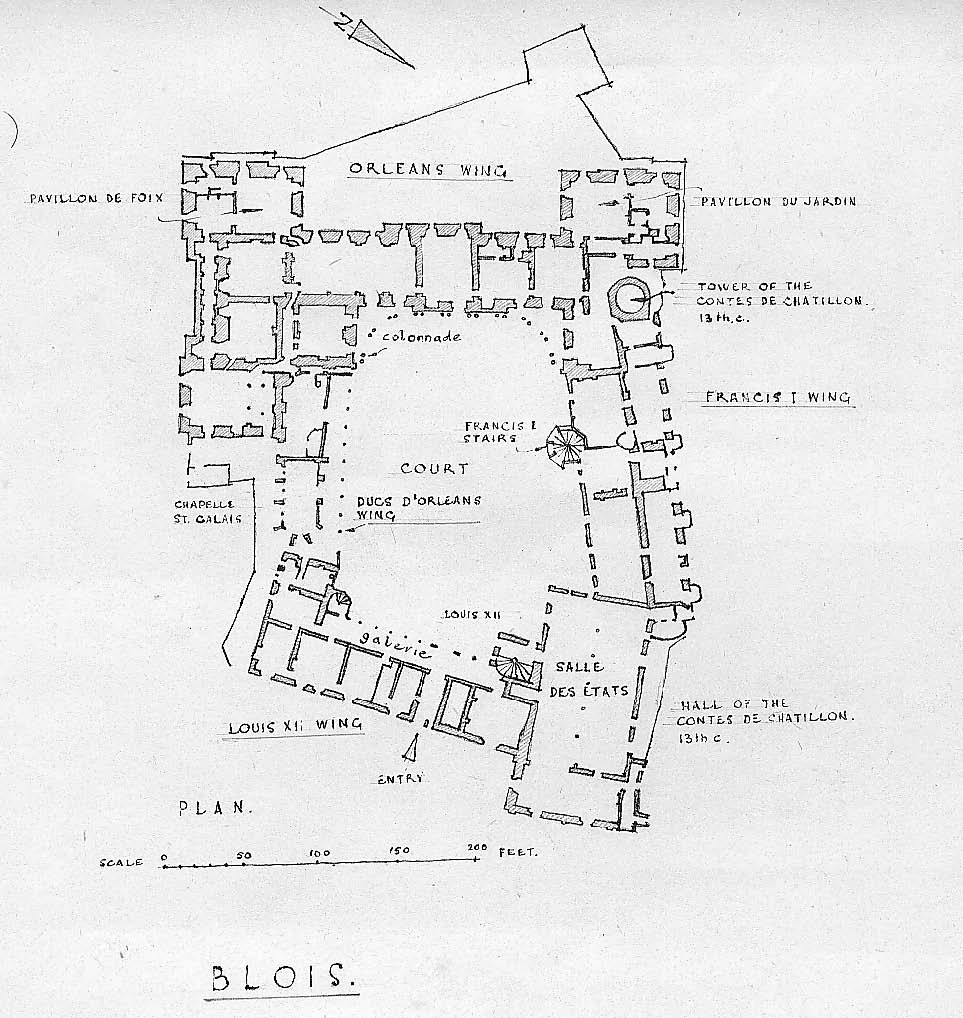

| - Plan | 12 | |

| - North Facing, the Grand Staircase | 37 | |

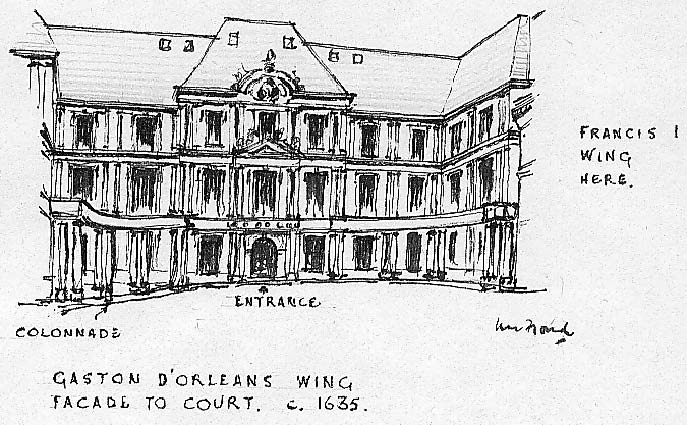

| - Gaston d’Orleans wing | 41 | |

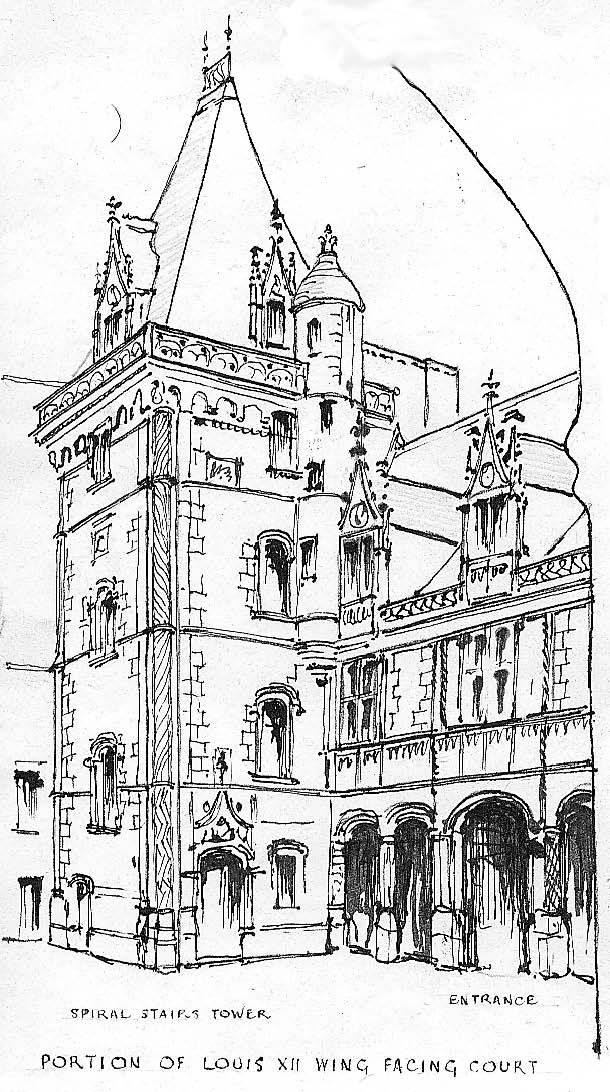

| - Spiral Stair LouisX11 | 42 | |

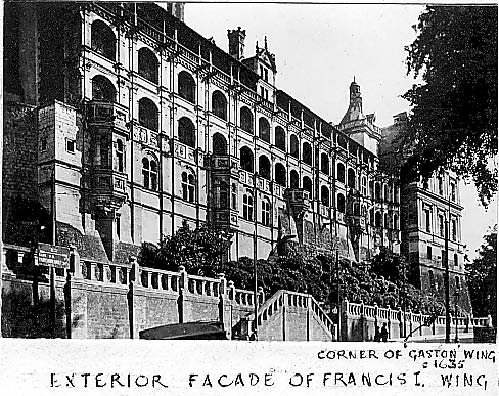

| - East Facade court, Exterior Francis I wing | 38 | |

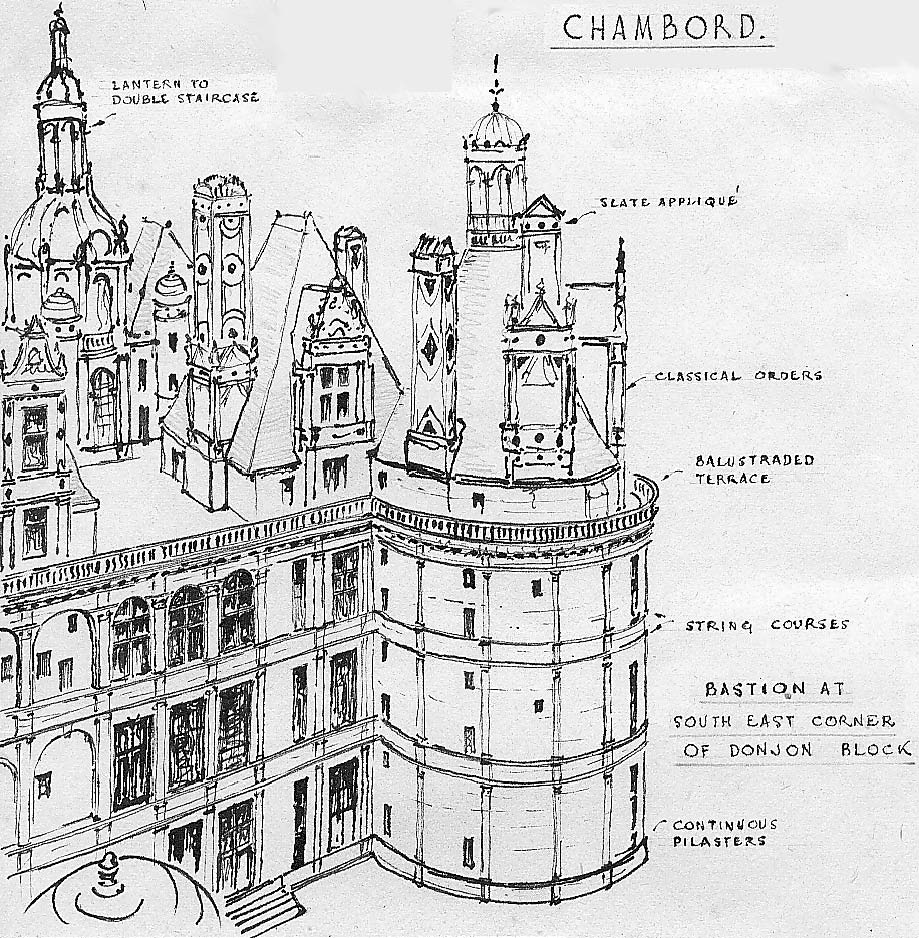

| Chambord | - Bastion SE corner | 31 |

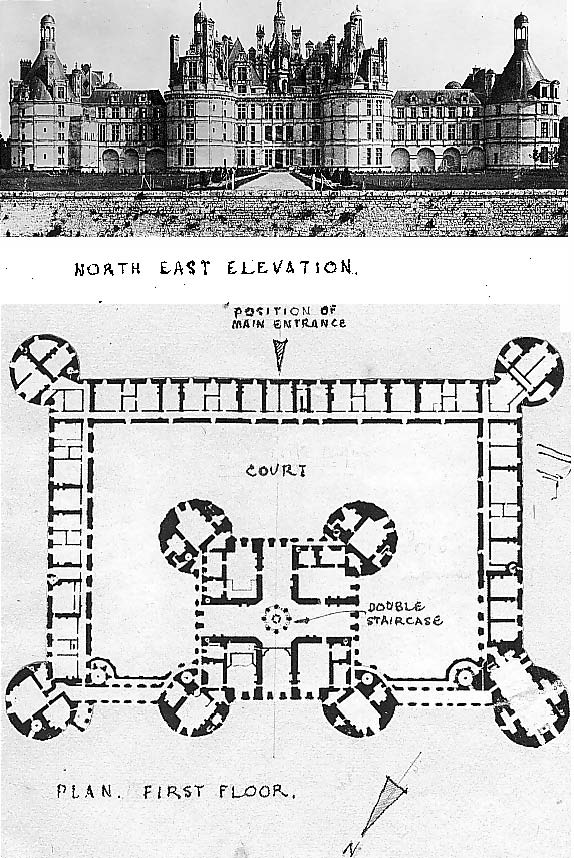

| - Plan and NE elevation | 32 | |

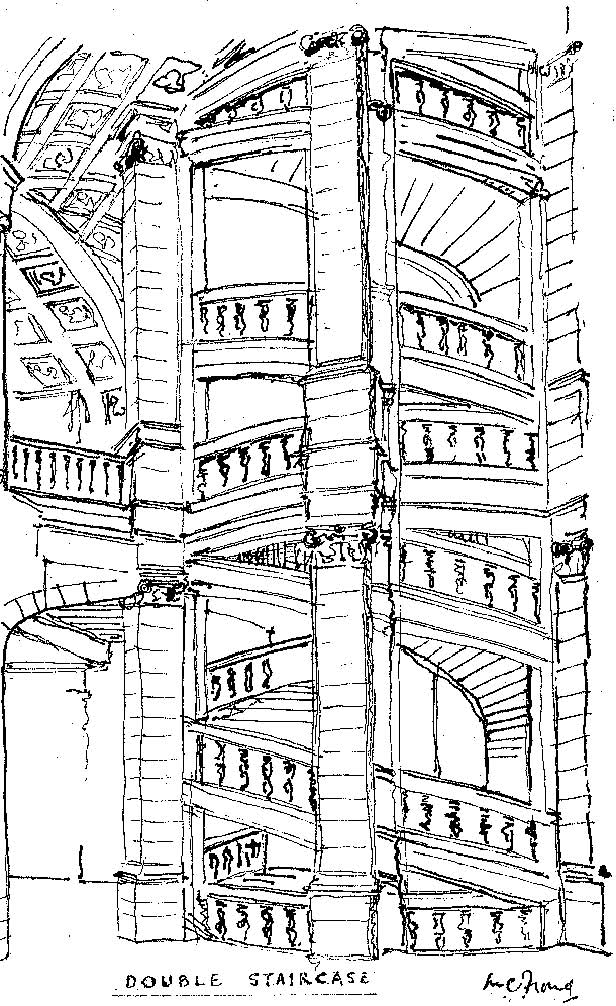

| - Double Staircase | 33 | |

| - Elevation from court | 34 | |

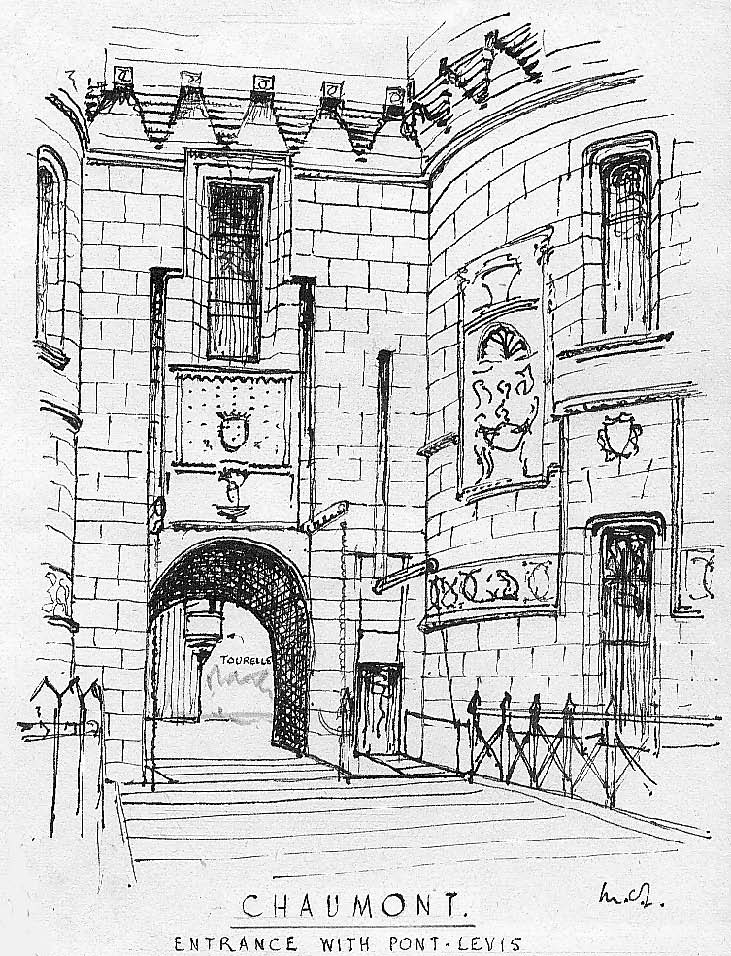

| Chaumont | - Pont levis | 19 |

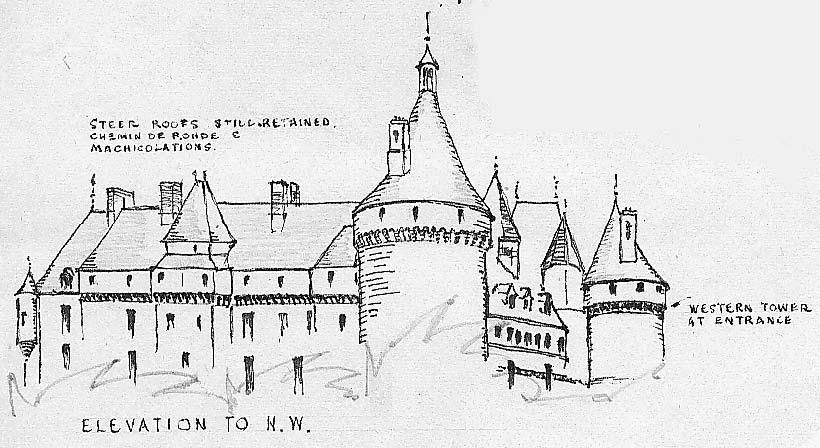

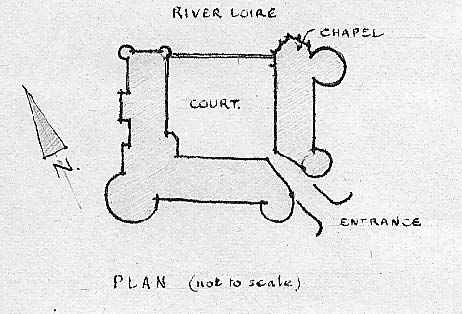

| - Roofs with machicolation, Plan, View | 20 | |

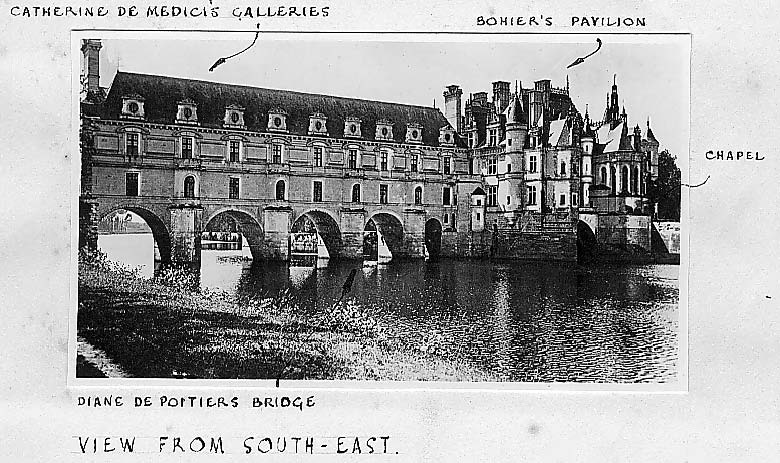

| - Diane de Poitiers bridge SE | 39 | |

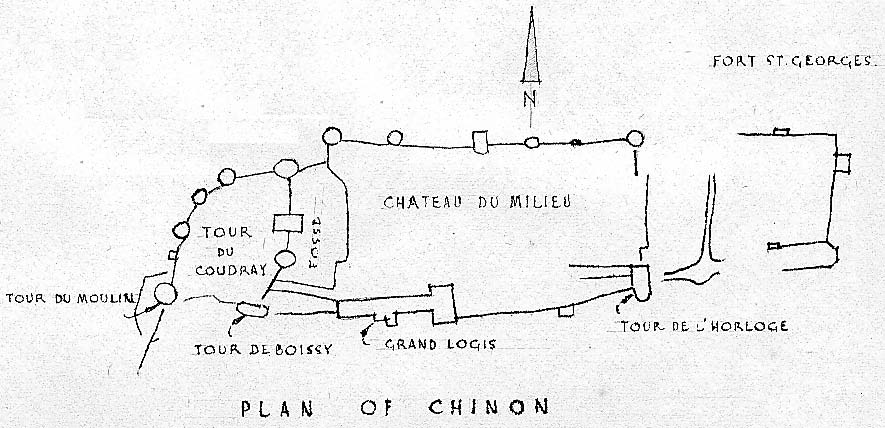

| Chinon | - Plan | 7 |

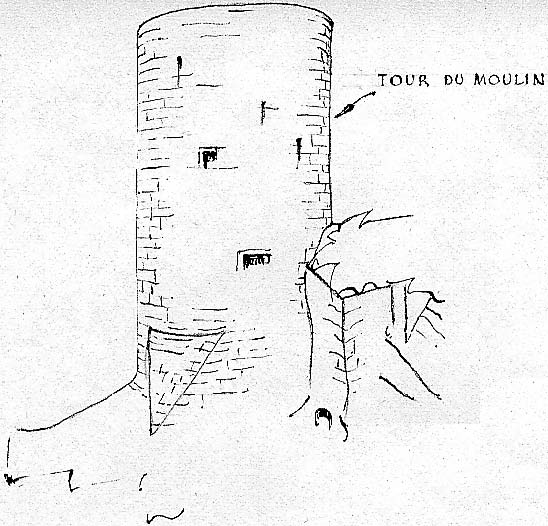

| - Tour de Moulin | 8 | |

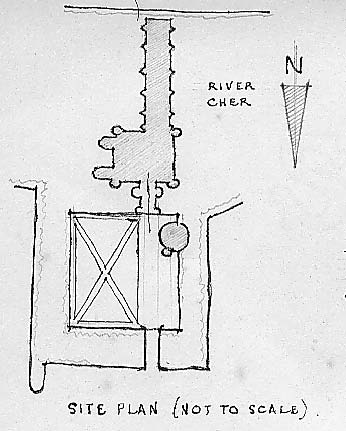

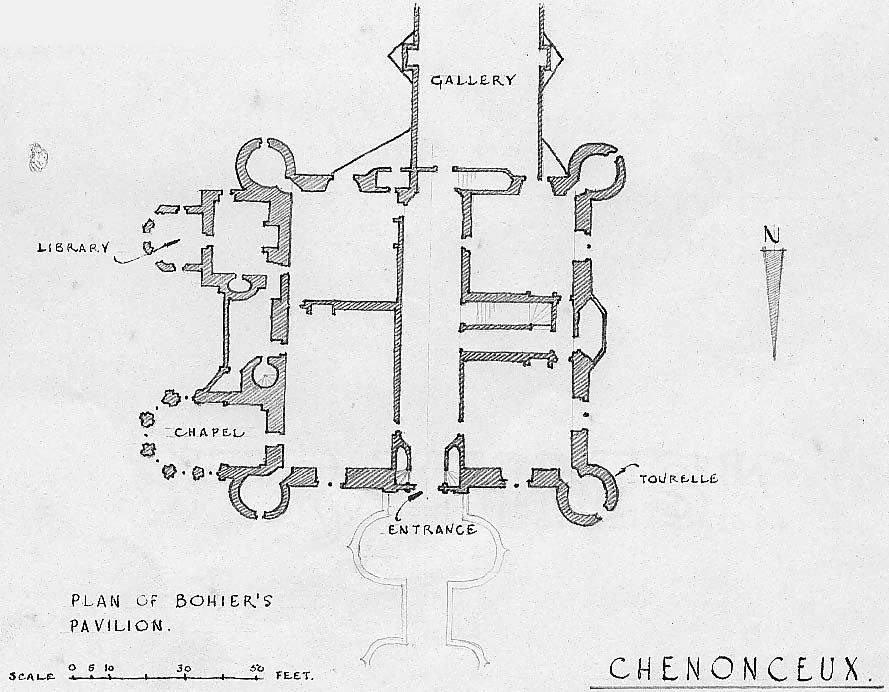

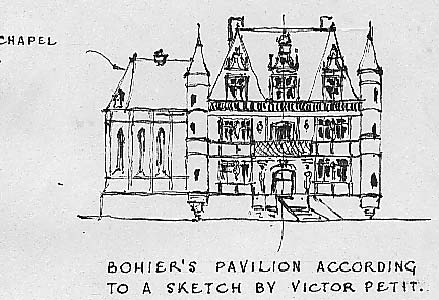

| Chenonceau | - Bohier pavilion plan | 30 |

| - Bohier pavilion sketch | 39 | |

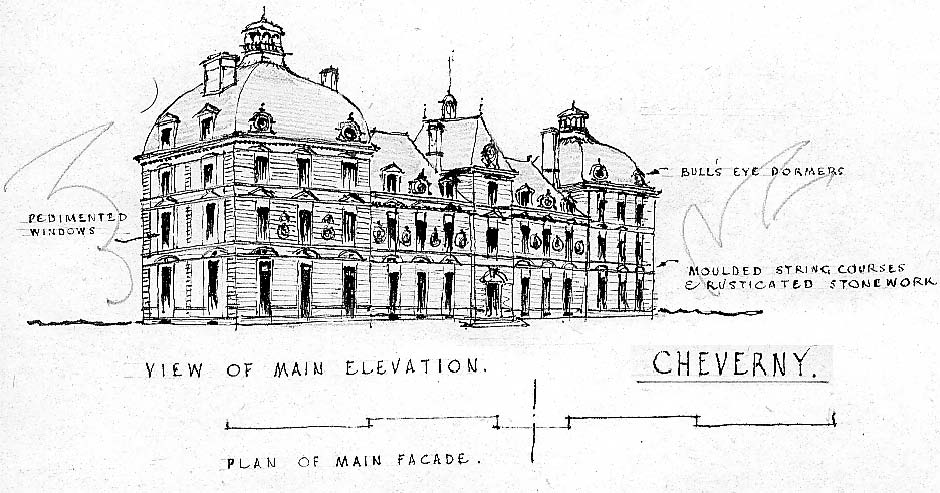

| Cheverny | - Main elevation | 43 |

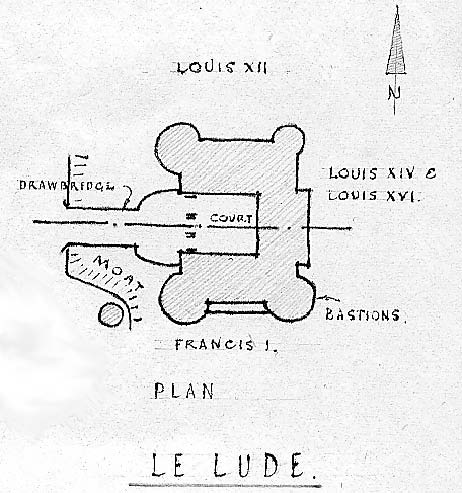

| Le Lude | - Plan | 40 |

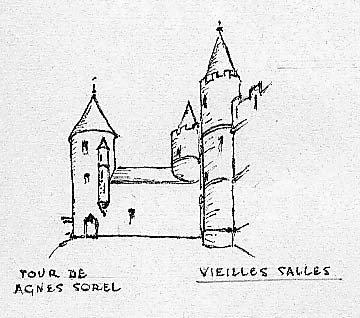

| Loches | - Tour de Agnes Sorrel | 8 |

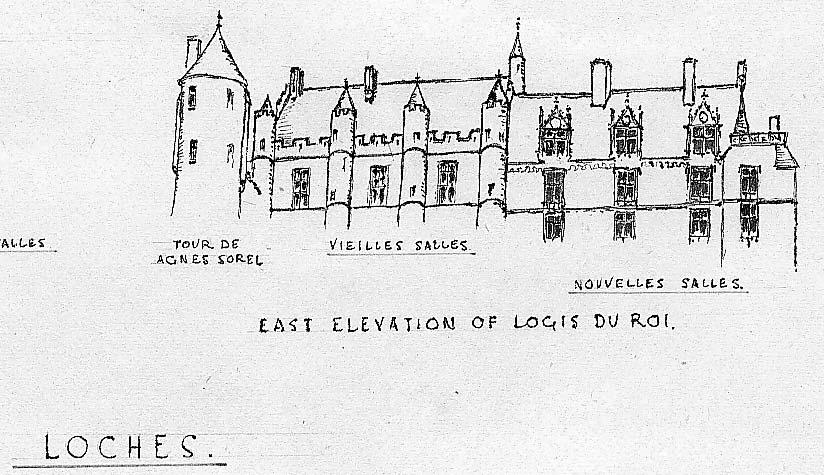

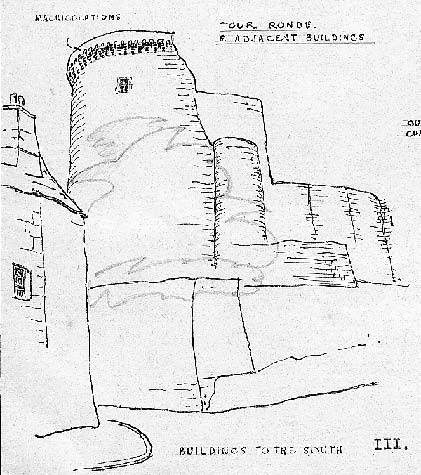

| - Tour Ronde - Logis du Roi | 14 | |

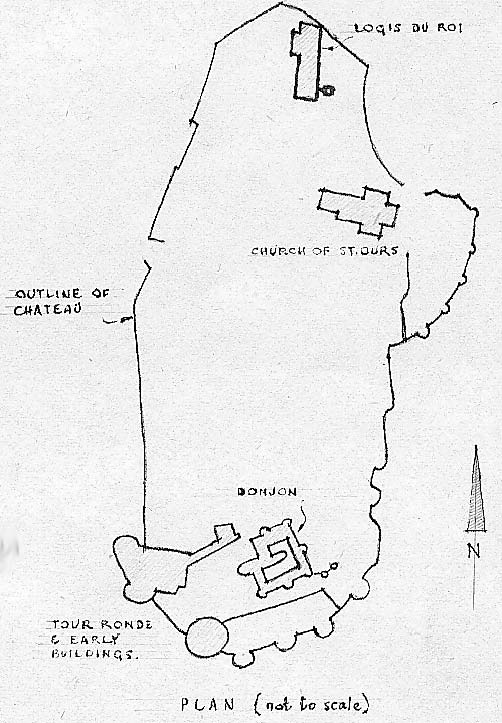

| - Plan | 15 | |

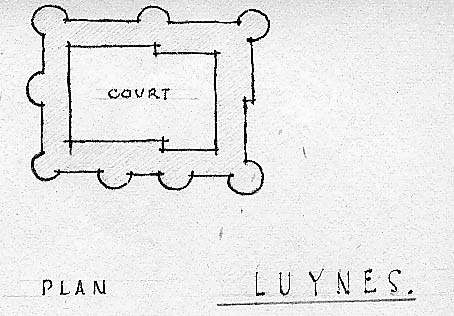

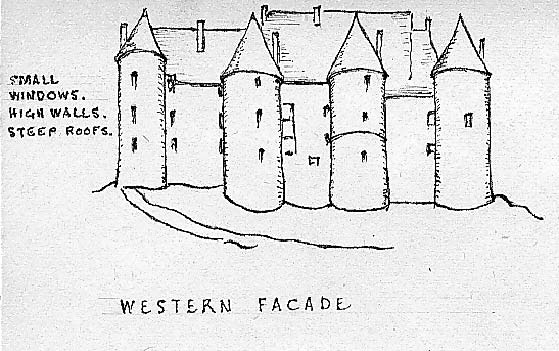

| Luynes | - Plan, Western Facade | 13 |

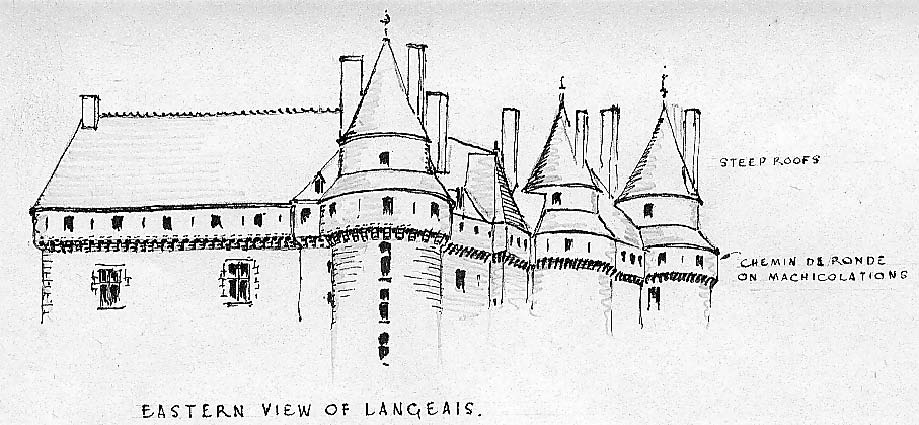

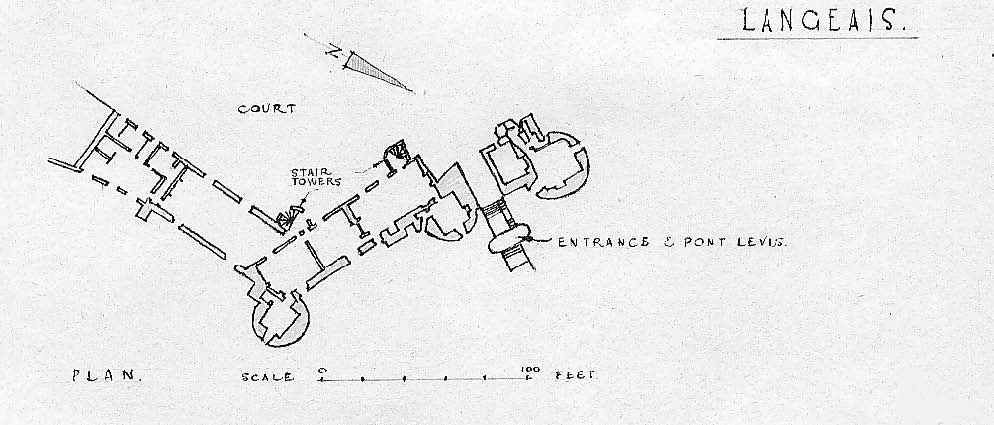

| Langeais | - Plan, Eastern View | 16 |

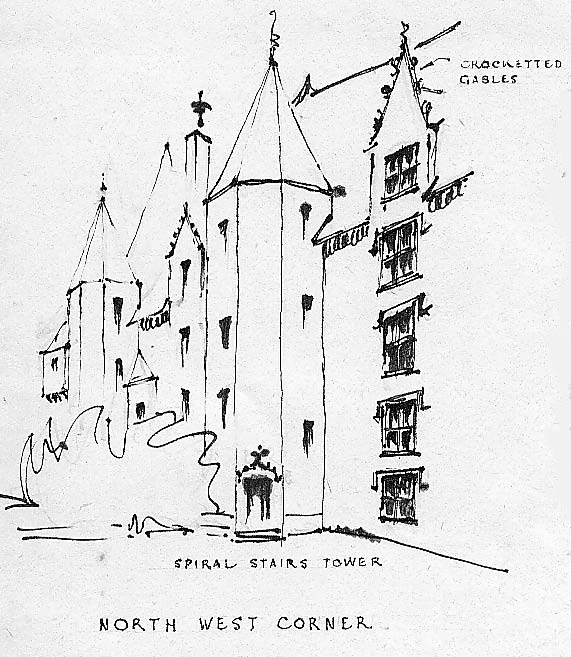

| - NWCorner showing crocketted gables | 17 | |

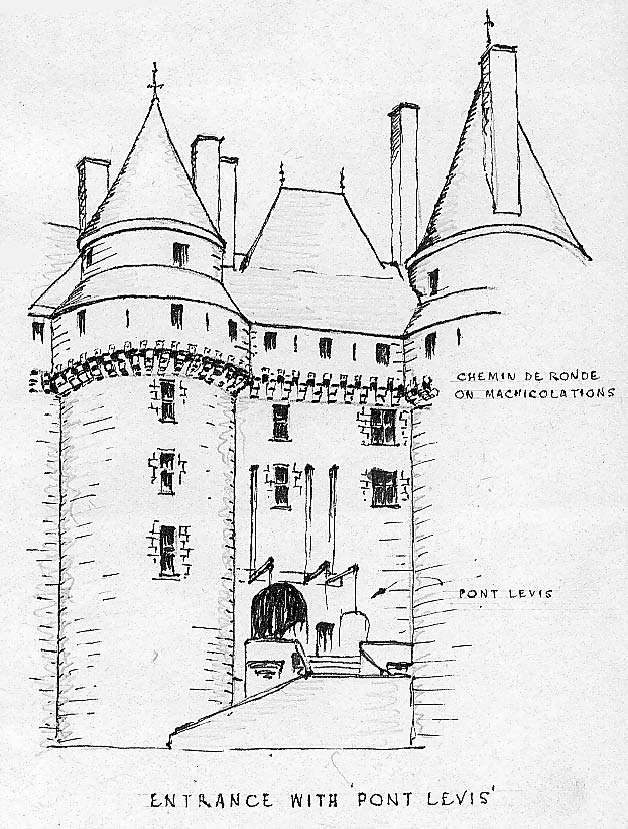

| - Entrance pont levis | 18 | |

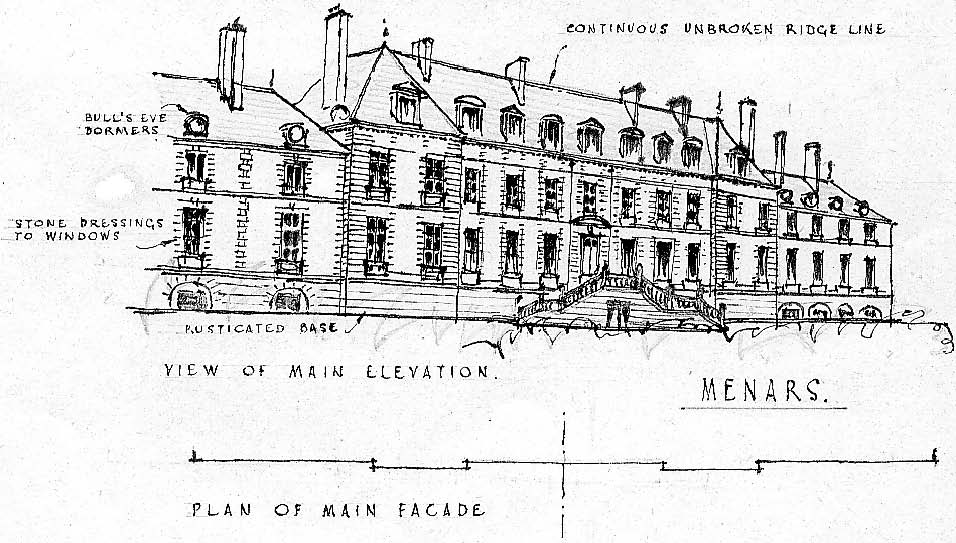

| Menars | - Main elevation | 44 |

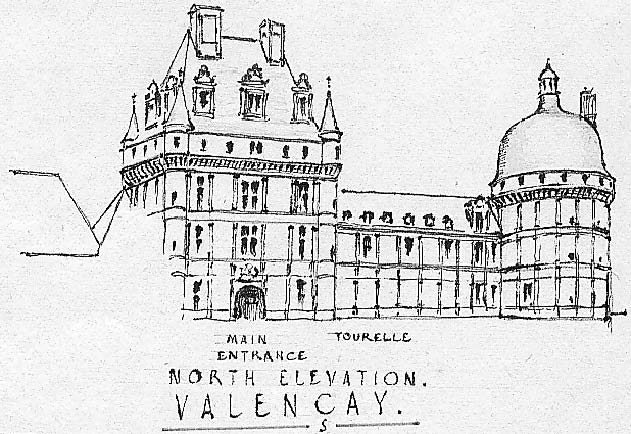

| Valencay | - Plan, North entrance | 35 |

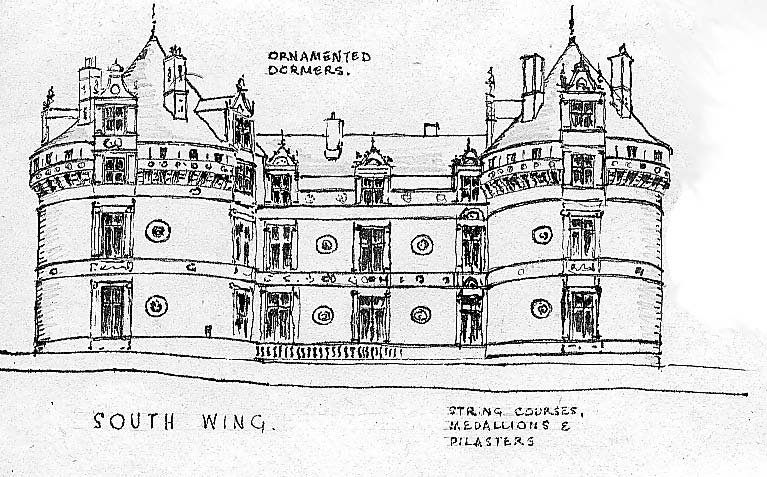

| - South wing with ornamented dormers | 36 | |

1↑

Introduction

A survey of the chateaux of the Loire valley brings before one a large cross section of French historical architecture covering a period of several centuries, from such fortified chateaux as Chinon and Loches which date from the tenth and eleventh centuries to the residences of Cheverny and Menars and others of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. All of these number some seventy or eighty chateaux of varying dimensions.

A large majority of these chateaux were built or extended at the time when the Court of France resided in the Loire Valley which was from about the middle of the fifteenth century to the middle of the sixteenth century. When the Court moved to Paris the Loire chateaux were still retained as hunting lodges, as the Loire valley with its rivers and woods a convenient distance from Paris, provided a suitable centre for such pursuits.

It is not possible to classify chronologically, except broadly, the majority of the chateaux, in view of the fact that the periods of erection, enlargement or alteration either overlap or the duration of construction of many of them was prolonged for several reasons over many centuries. Therefore, the chateaux, or portion of chateau referred to, will be considered individually and placed as near as possible in its correct relationship with the general development of the Loire chateaux as a whole.

The earliest chateaux were fortresses generally built on high ground in strategic positions above rivers to command valleys. They had thick walls and small windows to resist attack but with the discovery of gunpowder and the development of a new social order the fortress chateaux gradually changed into palatial residences.

This development of the chateau in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries into buildings arranged rather for residence than defence led to a corresponding widening of the term “chateau” which came to be applied to any seignorial residence and eventually to all country houses of any pretensions.

The French distinguish the fortified from the residential by describing the former as chateaux fort and the latter as chateaux de plaisance. It is important, therefore, that in any research into the development of the Loire chateaux due regard is given to the earliest chateaux fort of the medieval period.

Chateaux Fort

The planning and design of the earliest chateau fort was devised wholly from the point of military exigencies, the convenience of the inhabitants being considered only so far as it was consistent with military security.

Before the tenth century, France was peopled by races differing in origin, government, customs and language. As a result these different influences were not without their effect on the architecture of the times. There was little to unify the country and consequently defence was the main consideration in the design and construction of the chateau fort. So long as every duke was constantly engaged in combat with the neighbouring states it was inevitable that little thought or time could be spared for the comfort of the occupants of the chateau.

By the eleventh century, the Normans had lived in the Northwest of France for a hundred years and had become rulers of a large territory. Being progressive by nature they adopted the achievements of the Franks where it was advantageous to do so. They conquered Sicily and parts of Italy and created a notably interesting civilisation there, a blend of what was most advanced in their own administration and in the thoughts and habits of the conquered Saracens. Much of what they saw had a considerable influence on France in the eleventh century.

The foundations of the medieval civilisation were, however formed during this period. The feudal system developed under the Normans until it became the very centre round which the social life of the middle ages was built, although it was advanced in its character before coming under Norman influence. Feudalism had arrived in its final form and political stability to a certain extent was reestablished, as once before in the history of France there had been unity under Charlemagne.

The Norman style of building was the most consistent variety of Romanesque in the West, the

development of which, coming through several schools, strongly influenced France. Although the character of Romanesque differs in the North and South of France, by virtue of its geographical position the Loire river and its tributaries formed a natural and ideal barrier which encouraged the intermingling of the styles. Many of the buildings in this locality often display features common both in the North and the South.

There was a feeling of certainty and stability about the style - blunt, massive, overwhelmingly strong are the individual forms used in the early buildings, especially in the chateaux fort. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the feudal system necessitated a permanent stronghold for the feudal lord.

The early Romanesque chateaux had donjons or keeps, either shell or rectangular. The former was generally built on existing earthworks and consisted of walls of masonry circling the mound on which it was built and was a development of the motte and bailey castle with its bailey at the base of the motte and surrounded by a fosse. The rectangular donjon was used at the same time as the shell but was generally erected on sites other than those suitable for a motte and bailey chateau fort. The donjon had a compactness and a disdain of embellishment and although there were reasons of defence for this bareness of the donjon it was nevertheless consistent throughout their architectural forms and expressions.

In this early period the object of a chateau builder was to provide a number of self contained tours or forts, each able to sustain a siege after the fall of the others, the last stand being made in the great donjon, a tower larger than the rest which often contained the lord's own lodging besides accommodation for a small garrison, a well, stores and all that was requisite for a siege of some duration. The donjon was often several storeys in height and sometimes access was made to it at the first storey above the external ground level and often protected by a forebuilding.

With the object of prolonging the defence, access from one tower to another was made so intricate that only the inmates could find it, so much so indeed, that even they were impeded by its difficulties and sometimes its purpose was thus defeated.

An example of this early planning is the chateau of Chinon.

Existing before the Roman occupation of Gaul, it was from early times an important fortress occupied at one stage by Visigoths. Eventually, forming part of the Royal domain the fortress came to the Counts of Touraine and from these to the Counts of Anjou in 1044. In the next century it passed to Henry II of England who died there in 1189. Subsequently it was won back to France by Philip Augustus in 1204 after a year's siege.

2↑

The chateau, now ruined, consists of three separate strongholds. That to the east, the chateau de St.Georges, built by Henry II of England, has almost vanished, only the foundations of the outer wall remaining. The chateau au Milieu, comprises the donjon, the pavilion du l’horloge and the Grande Logis. Of the chateau du Coudray, which is separated by a fosse from the chateau du Milieu, the chief remains are the Tour de Moulin (10th c.) and two later towers.

3↑

Although Chinon occupies an important position in French military history, it is for the purposes of this thesis significant only so far as the general planning is concerned - it is a medieval chateau fort in the true sense, and typical of contemporary chateaux with its small windows and apertures and long, irregular plan, the last being the result of the site conditions. Purely functional, the walls and openings are hardly decorated or moulded in any way and no attempt was made to conform with any aesthetic principles.

The chateau of Loches also, is in the main and from the ground plan point of view an important

example of early chateau fort developed around the monastery of St. Ours, the collegiate church which,

built in the 12th. century, has remarkable stone vaulting in the form of hollow octagonal pyramids

forming the roof over the nave and west door.

The fortifications in the Southern part of the chateau have for their core a rectangular donjon built at

the end of the llth century by Fulk Nerra. This donjon is one of the earliest rectangular donjons in

France and is most imposing. Standing almost complete, the donjon actually consists of two towers

joined together. The larger was divided into four storeys with the entrance on the second one. The

smaller tower or fore-building now has only three storeys, with a chapel on the third.

In the northern part of the chateau are buildings of the 15th and 16th centuries to which reference is

made later.

At one time probably the most formidable fortress in Europe, the chateau of Angers was planned in the

manner of the earliest chateaux fort for the Counts of Anjou.

4↑

4↑

The strength of the fortifications was concentrated largely in the curtain walls which were constructed of slate bonded horizontally at intervals by courses of dressed sandstone and granite, the alternate arrangement giving them a strong banded effect.

5↑

5↑

The walls are of great height and strength and were at one time defended by seventeen powerful towers placed close together. Walls and towers have widely battered plinths rising to about half their height and the rock at their base is steeply scarped. Not only are these walls powerful in themselves but despite the fact that most of the towers have lost their upper portions the general effect today is most imposing.

6↑

6↑

Eventually Henri III considered the chateau had outlived its usefulness and in 1589 or thereabouts

found it necessary to have much of it demolished to the state we see it in today. In the system of defence exemplified by those early chateaux it had been found that in practice once the enceinte was broken neither the towers nor the donjon could be held for any length of time, the invention of artillery contributing to the downfall of the system. In its stead was devised the so-called concentric system in which a chateau was defended enceinte by enceinte instead of tower by tower, the innermost enceinte falling as a whole. The donjon in fact became an anachronism although invariably remained as before, the core of the chateau, irrespective of the period or system of planning.

But even though the methods and science of warfare had changed and the ideal plan was the concentric

one, many if not most of the Loire chateaux were planned in the old way. It has been suggested that the Crusades resulted in the reform in the planning of chateaux, the Crusaders having built on the concentric system in the Holy Land, copying from their foes the Saracens, who in turn had derived it from the earlier Roman examples. However, it should not be forgotten that as early as the eighth century, some three hundred years previous to the Crusades the Saracens had overrun and occupied Spain and quite a large part of France as far north as Tours on the south bank of the Loire river and it may quite well have been their influence that had left its imprint on the castle plan of the Franks.

Some authorities suggest that the Saracens in the Holy Land adopted a more mobile role in their warfare against the Crusaders and thus seldom built castles being content to occupy those captured from the Crusaders when called upon to adopt a defensive position.

In the concentric system of planning the walls of the inner bailey and its towers were made of sufficient strength to resist the somewhat feeble artillery of the day and were virtually unpierced below their summit. This was crowned by an allure or chemin de ronde on bold machicolations which made the complete circuit of the walls and towers and gave easy access for the garrison from one part of the chateau to another. In some chateaux there is more than one tier of allure.

The upper portions of the towers in direct communication with the allures were used only by the most reliable men, generally the lord's own retainers who also had charge of the gatehouse and other posts of trust. The mercenaries, on the other hand, who could not be depended upon not to offer their services to the highest bidder were confined to their own quarters and only employed where there was least opportunity for treachery, while the internal communications between their quarters and the rest of the chateau were so contrived that they could not easily approach either the private apartments of the lord or reach the ramparts except under the command of a trustworthy officer.

The chateau itself was approached through a fortified outer bailey in which were the stables. This communicated by a drawbridge across a dry fosse with a middle bailey which was separated from the inner bailey or chateau proper by another dry fosse. This was spanned by a drawbridge defended by a barbican. In the three baileys one may see the prototype of the basecourt, forecourt and cour d'honneur which occur more or less complete in chateaux of a more peaceful age.

The inner bailey which contained all the vital parts of the great organism of the chateau consists of a space enclosed within high curtain walls with round towers at its angles and its flanks, while the remaining buildings were set against the inner faces of these walls and look for the most part into the interior courtyard.

The space thus enclosed is not necessarily a regular one but conforms in outline to the irregularities of the site, and the buildings, though they may by chance show a rough symmetry in plan, are far from symmetrical in form.

Many characteristics are common to chateaux at this time. Firstly, the irregularity and unconscious lack of symmetry, secondly an absence of a general scheme of planning completely thought out as a whole and controlled by aesthetic principles instead of which we have planning which aims rather at isolating the various compartments and connecting them only so far as is absolutely necessary. Although convenience is aimed at, it is only partially achieved in a piecemeal fashion and then only so far as military and other considerations would permit.

There is no organised system of intercommunication either vertically or horizontally. This point may be illustrated by the use of frequent spiral staircases and the scantiness of corridors, the staircases in the earliest chateaux generally being constructed in the thickness of the wall or possibly in turrets and the corridors usually narrow passages. Those that exist in later chateaux being mostly in the nature of covered ways and open to the air.

The third similarity was the avoidance of all large openings on the outer walls. There is only one real entrance, the posterns being many feet above the external level and impracticable from the outside except with assistance from within.

Such general similarities as mentioned above are all that one can really expect even between contemporary medieval chateaux. For aside from any caprices on the part of the builder or owner, the very conditions under which they were raised tended to produce dissimilarity. The dominance of military necessities or tradition still compelled the sufferance of many inconveniences.

Generally no total artistic effect is produced by the grouping of buildings in accordance with practical requirements, some parts are formidable and simple as insecurity of the times might demand and others were richly decorated as security was ensured.

The feudal fortress gradually became unnecessary either against the foreign invader or the domestic free-lance, as France was now, after long periods of famine and warfare within her borders beginning to enjoy the blessings of a more established peace.

The thirteenth century chateau was often enlarged by additional buildings which clustered round the donjon. The inconvenient four storied donjons necessary in those more turbulent times were owing to the increase of hospitality frequently abandoned as residences in favour of a hall and additional living rooms placed conveniently in the inner court.

7↑

7↑

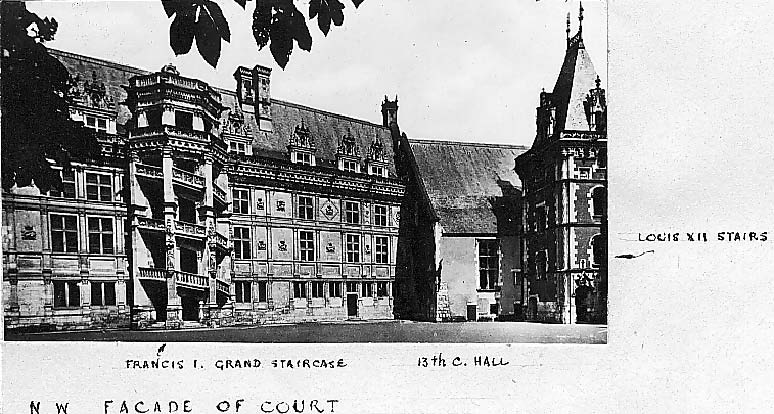

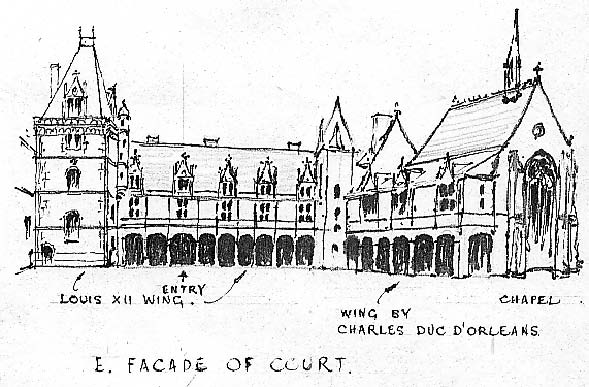

Of the thirteenth century at Blois little remains except the Great Hall at the Northeast angle of the present chateau, the tower at the North-west angle and also the Tour de Moulin and an isolated tower to the South which at one time guarded the only entrance. A curtain wall, with two intermediate towers attached, connected the first and second buildings, the whole of which was incorporated in the later works.

It is possible also that the chapel on the South Side also dates from the thirteenth century. Although Blois is one of the most splendid chateaux in France, it is not really a single chateau but a collection of many of various periods and has the unusual merit of exhibiting first class examples of three periods of Renaissance, besides of course, the earlier works already mentioned. All of which are grouped round the large polygonal courtyard.

8↑

8↑

The plateau, of which the present chateau occupies the eastern half, was the original site of a fortress

even in Roman times. Apart from these examples at Blois, and the chateaux fort previously referred to, little remains to be seen of thirteenth century work in the Loire chateaux due to considerable building activity which was carried out as the feudal system decayed, in adapting the existing chateaux to suit the changing social conditions. The following century continued the period of building work in which many chateaux fort were gradually changed into purely dwelling places.

9↑

9↑

An example of this early development is the small chateau of Luynes which as it stands today still

preserves in its exterior the appearance of the feudal fortress of the thirteenth century.

The first building on the site was destroyed by the Counts of Anjou. The chateau which was rebuilt in

the twelfth century was remodelled in subsequent centuries and today most of the existing chateau

retains characteristics of the thirteenth and and fifteenth centuries.

10↑

10↑

The western facade consisting of four massive round towers in a curtain wall and capped by steep

roofs, illustrates well the feudal appearance.

When the chateau at Maille, as Luynes was originally named, was bought by Hardouin IX de Maille in

1463, an additional building of one storey and an attic to be used as a lodging instead of the draughty

halls of the ancient fortress, was built on the inner face of the west wing. This work was in the style of

the nearby chateau of Plessis les Tours which had previously belonged to Hardouin.

Of this block which was built in brick and stone little remains of the original work except the turret

staircase, the remainder having been disfigured by restorations in the nineteenth century.

The south wing was demolished at some time, probably in the seventeenth century when more

additions were made in the courtyard but as these hardly illustrate the development of the Loire

chateaux they are not worthy of mention here.

The conversion of Blois from a chateau fort into such a building began in 1440, when Charles, Duke of

Orleans, returned from captivity in England.

He built in the Gothic manner a residential block which closes the west end of the court and added a

rich lantern to the tower in the north-west.

He also built a three storied block of apartments along the inner front of the curtain wall and a cloister

walk with gallery over along the inner side of the chapel, and it may be possible he was responsible for

rebuilding the chapel on the old foundations. At that time it comprised a nave in addition to the existing

choir.

The gallery on the south side of the courtyard is constructed of brick and stone and is quite simple in design. The inner side of the ground floor is arcaded with depressed arches carried on octagonal pillars. The first floor which is closed in has little ornament other than two courses of mouldings at its base. The windows have mullions and dressings of stone, a feature common to contemporary chateaux and which may be seen in the Logis du Roi of Loches,

11↑

11↑

At the northern end of the vast chateau of Loches is the Logis du Roi which consists of two parts, that is the vieilles salles built by Charles VII, in the fifteenth century, and the nouvelles salles built purely as a dwelling at the end of the sixteenth century. The former is of fortified appearance with its chemin de ronde and tourelles. Contemporary with this work is the adjacent tower which contains the tomb of Agnes Sorel who was, the favourite of Charles. Previously it was in the church of St. Ours but was for safety removed to this tower during the Revolution when the church was damaged. The nouvelles salles was built for Anne of Brittany, whose emblems of speckled stoats and tassels may be seen on the walls of the oratory formed in part of the building.

The resultant facade of the logis is thus a blend of Gothic and early Renaissance. Although the eastern wall of this building is continuous and unbroken in plan there was no attempt made to keep the ridge of the steep roof of the new work in line with that of the earlier work with its stepped gables.

12↑

12↑

Horizontal emphasis was ensured in the later portion by the continuation of the string course between the first and second storey windows. Gothic verticality of the four tourelles is maintained by the three dormer windows with their steep crocketted gables. The eaves of the later work are carried on false machicolations while the earlier has a battlemented parapet wall between the tourelles forming an allure.

The chimneys of the new work are grouped to form square stacks while some of those in the earlier

building are similar to contemporary chimneys in England and are octagonal in plan. The windows of the later work are an indication of the transitional period in France with its stone mullions, transomes and hood mouldings. They are more representative of the late Gothic than Renaissance although the jambs and sills are finely moulded and the dormers with their pilasters indicate that the classical influence is beginning to assert itself.

A sketch by Victor Petit drawn about 1860, shows the Logis du Roi with a plain parapet wall carried on a continuous corbel table, but as considerable restoration has taken place since that day, it may be that the merlons that form the battlements of the present vieilles salles may be the result of an overzealous attempt by the architect in charge of the work to restore it.

13↑

13↑

In the fifteenth century Louis II included the eleventh century donjon and adjacent buildings in some extensions - a powerful corner tower called the Tour Ronde and the Martelet, all of which fifty years later after the pacification of the realm and when the last remnants of the old feudality had been crushed, became the State prison.

In addition to this work, Louis XI built the chateau of Langeais in 1464.

14↑

14↑

This is not wholly typical of the period being rather in the nature of an addition than a completely new

residence.

The massive donjon, one of the earliest rectangular donjons in France and built by Fulk Nerra at the

upper end of the enceinte, was still useful from the military angle but was quite unsuited for habitation

by Louis.

15↑

15↑

The buildings at the lower end of the enceinte were therefore replaced by a new block conforming in

plan with the outline of the old.

The walls were still thick, that is about eight feet and it was provided with a portcullis and drawbridge.

Its outer walls were crowned with a chemin de ronde but it would not have withstood a serious siege as

the windows were comparatively large and numerous.

16↑

16↑

The internal arrangement is more comfortable and five stories of dwelling rooms were provided, but even though there was some advance in planning there was still insufficient intercommunication. Corridors were lacking and stairs were spiral and small.

17↑

17↑

There was little decoration or embellishment of the walls except in isolated places such as door heads and similar positions. The windows of this period were arranged vertically above one another where possible but were not connected in any way.

Another example of later chateau fort, the chateau of Chaumont, southwest of Blois and situated on a height overlooking the Loire valley was a defence post at one time of the Counts of Blois.

18↑

18↑

It was given to the Lord of Saumur after he was driven from Saumur by Fulk Nerra. This first chateau was destroyed during war with Henry Plantagenet. In the second chateau Thomas a Becket met Henry shortly before returning to Canterbury. This chateau was destroyed by Louis XI in 1460 or thereabouts as a reprisal against Pierre, father of Georges d'Amboise.

A few years later, about 1473, the present chateau was commenced for the d'Amboise family. This is a compact building with a certain amount of perpendicular emphasis given by the corner towers. Mainly Gothic in feeling, there is a slight tendency towards the classic ideals of the transitional period.

19↑

19↑

The chateau has the appearance of a formidable fortress. It is however deceiving, as Chaumont is only fortified in the north west wing and in the Western tower where the walls are crowned by a chemin de ronde with battlements and machicolations,

20↑

20↑

In the Southern part, the entrance, and the south west wing the towers appear still more formidable than those of the west but in reality the walls are only half as thick.

21↑

21↑

Additions were made later to Chaumont in the sixteenth century.

Chateaux of the Transition.

During the period of transition from Gothic to Renaissance, that is from about 1495 to 1515, the chateaux were in many cases fortified and still of irregular plan. Very rarely, they were set out symmetrically and then only when confined to level sites.

A chemin de ronde was still built round the enceinte.

The accommodation for the inhabitants was usually placed in the inner court of which the donjon

possibly formed part. The salle basse or lower storey of the donjon was often the salle de garde or

guardroom while the grande salle or upper storey was the centre of life in the chateau.

The chapel occupied an important part in the lives of the people and was often placed In the heart of

the chateau, but was sometimes for convenience in the outer walls.

A long gallery for exercise formed a feature of many chateaux and overlooked the cour d'honneur.

Apartments, either single rooms or suites with ante chambers and wardrobes were situated in separate

towers seldom with any communication between them except by spiral stairs or covered ways along

the court.

Each wing was served by a turret stair or vis, with a State stair or grande vis occupying its own tower.

This was nearly always spiral in form and seldom completely enclosed and often projected from the

facade into the court.

These buildings were late Gothic in everything but the introduction of Italian ornamental detail. Any

research into the causes of the changes in the architecture of France at the close

of the fifteenth century reveals some significant facts.

Long before the actual forms of Italian classicism were initiated into France there was already a

reaction against the Gothic. The finest Gothic impulse was spent before the close of the thirteenth

century and the florid extravagance of the Flamboyant style which now prevailed, indicates a

weakened condition of the national artistic mind which made it easy for the introduction of foreign

imitations.

The invasion of Italy by Charles VII accentuated the developing appreciation of the Italian arts.

Although it is true that Italian artists were employed later to erect and embellish chateaux, the

evolution of French architecture towards an imitated classicism might have ensued in the natural

course of events if only by reason of the proximity of Italy and its works of art, the invention of

printing, and the general diffusion of learning. As early as the fourteenth century this art had been

introduced by the French popes. At a later date Italian inspiration is to be seen in the sculptured works.

A different aspect is presented however, in the case of architecture which for some while had

represented the supreme skill of master masons and expert craftsmen.

Beginning then with these facts it is evident that many issues operated to effect changes which have

proved peculiar to the French chateaux.

22↑

22↑

To the west of Chaumont, the chateau of Amboise overlooking the Loire valley from a rocky platform above the town was built on the site of an ancient fortress by the Counts of Anjou in the Eleventh century. After the territory around Amboise was united to the Royal Domain by Charles VII in the mid-Fifteenth century the chateau became a favourite residence of the kings of France.

23↑

23↑

Amboise consists of a Royal lodge, chapel, massive round towers and some other buildings within its

ramparts. The present chateau is of great importance by reason of the place it occupies in the general

history of French art and architecture.

In 1492 when the young Charles VIII was no longer under the guardianship of his sister, Anne de

Beaujeau, he undertook the reconstruction of the chateau with the intention of building a magnificent

piece of work. This work was already in full swing when the King was invited by Ludovico Sforza,

Duke of Milan, to assert Angevin claims in Sicily and in the Kingdom of Naples by force.

In 1494, Charles crossed the Alps with his army and invaded Italy and the French for the first time

became acquainted with Italian works of art.

Previous to this in 1453, owing to the fall of Constantinople, the Western world was flooded with

Greek scholars and literature which gave an added impulse to the new aspirations of Italian designers,

already encouraged to a new awakening in architectural energy by the early renaissance in literature by

their own great men such as Dante.

The Gothic had never really flourished to any extent in Italy and consequently it was in Classic forms

that the Italians expressed themselves in the great revival of art. They solved new problems by

mingling the results of deep study of ancient classic examples with the spirit of medieval architecture.

The awakening in architecture was only one manifestation of the spirit which was abroad in painting,

sculpture and all applied arts as well as in literature.

It was to this new world of history and poetry that Charles brought his army to whom the luxury and

splendour of Italy must have come as a revelation and contrasted very strongly with the roughness of

their own domestic establishments in France.

At the conclusion of a successful campaign Charles left Florence as a conquered city having rifled its

treasures with freedom. He conveyed stolen works of art and valuables back to Amboise. He also

brought back with him "twenty-two foreign workmen", that is sculptors, masons, artists and

metalworkers to build and work in the Italian style.

In view of the fact that Charles had shown open contempt for the Italians during his occupation,

heavily taxed the province and overlooked the cruelty of his troops, there may be some doubt as to

whether the craftsmen who returned with him to France had any other alternative.

However, it is this band of men arriving at Amboise towards the end of 1496 who started the great

movement whereby the French art became transformed.

Possibly the chateau of Amboise is then, one might say the cradle of Renaissance outside of Italy,

although in its mass the chateau remains distinctly Gothic.

It was primarily for the beautification of Amboise that the colony of Italian craftsman was founded and

it is their fusion with the native art that endowed France with the brilliant architectural development of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

As a result of Charles' rebuilding little survived of the earlier medieval buildings except the Chapel of

St. Hubert. The block of buildings extending south-west, and south of the chateau behind the two

courts and the block west of the north tower seem to belong to this period.

Charles also began the Tour Hourtault and the Tour des Minimes with the spiral sloping carriage ways.

Obviously Gothic, the Logis du Roi with its brilliant facade was also Charles' work.

The Italian influence is only apparent here and there in several details of decoration, certain keystones

in the Tour des Minimes decorated with a dauphin, a head of medusa, a mask and the main doorway of

the Tour de Hourtault ornamented with sculptures foliage and the pilasters with arabesques.

After Charles VIII's premature death by accident at Amboise in 1498, Louis XII who married the

widow of Charles VIII, continued the works which had commenced and added other portions including

the galleries enclosing the garden and probably the block to the south of the North tower.

Following the death of Louis XII, Francis I made further additions at Amboise. Later kings added little

to the chateau and a scheme of improvements by which one court was to have been formed out of the

two by the removal of the sunken tennis courts and cross galleries and completed by a new gallery

joining the church of Notre Dame with the South wing was not carried out.

The main building perpendicular to the north wing was constructed at the beginning of Francis II’s

reign and is typical of the early Renaissance style.

Leonardo de Vinci who was summoned to Amboise by Francis I to carry out various works of art, died

there in 1519, and it is claimed that his remains are now buried in the Chapel of St Hubert.

24↑

24↑

In the course of time Amboise ceased to figure in the history of art but regained fame in 1560 after the

failure of the Huguenot conspiracy, when the battlements of the Logis du Roi were hung with the

remains of the conspirators.

Bombing during World War II did severe damage to the fabric of the chateau, but at the time of the

visit of the writer work was in progress for the repair of the war damage.

In 1496, Louis XII completed the courtyard at Blois by building across the eastern end between

the@chapel and the hall a wing with a cloister walk and stair towers on the inner face which is pierced

by an entrance gallery.

This work in the transitional style was finished about 1503. The construction is of red brick patterned

with black slate and with dressings of stone and matches strictly the line of the adjoining gallery of

Charles. The decoration is interesting because of the combination of traditional Gothic motifs with the

elements of Italian importation. The first manifestation of the Renaissance in the chateau is shown by

the pillars in the lower gallery being decorated by lozenge shapes carved with fleur de lys and spotted

stoats in the Gothic style and by Italian arabesques and scrolls, etc.

The features spaced irregularly illustrate the Gothic feeling. Details with few exceptions appear Gothic,

but closer inspection does reveal, however, further Renaissance elements.

Louis formed the opening in the above block which is now the entrance to the court, and which, on the

external facade is surmounted by his sculptured figure on horseback in a niche. This recess has a

Gothic pilaster surround and double crocketted gables; the whole being on a fleur de lys background.

The classic carving is on the string course, below the sculpture and is faced with acanthus leaves, also

the panels on the centre portions of the pilasters. The initials of Louis and Anne adjoin Louis' emblem,

the 'Royal Porcupine'. In most other respects this wing remains Gothic.

In 1515, Francis I, who had married Claude, daughter of Louis and Anne, the previous year,

commenced at once to alter the north wing refacing both fronts and adding the stair tower in the court,

which one might assume was based on the design of the Gothic spiral stairs of Louis XII.

The Francis I staircase is a great polygonal structure that rises right up through the facade of the wing.

The four vast piers, rather in the nature of buttresses reach from the ground to the main cornice which

projects far enough out to cover them. The piers are treated like pilasters with Corinthianesque capitals,

and are banded along the middle with classic profiling. Yet on the face of each of these members is a

corbelled niche, reminiscent of the medieval period, complete with a rich canopy and a statue in the

late Gothic style,

While these works were in progress it was decided to add a new suite of apartments outside the curtain walls and opening on to a terrace running from the Great Hall (previously referred to) to the north-west tower which was also enclosed in the open galleries. Soon after a one storied loggia was built out on the terrace.

25↑

25↑

The proposed works along the north front of the Great Hall were interrupted in 1524 owing to the

death of Queen Claude.

Considerable work was carried out at Blois by Henri II and his sons. This work included the block on

the south west angle of the chateau, a portico between the Francis I staircase and the ends of the court,

an entrance gateway at the end of the Great Hall to form an approach from the donjon tower, an

observatory for Catherine de Medici on the Tour de Foix, an officers' lodging in the garden and a

pavilion at the foot of the Stag gallery.

Although much of this work remains, restorations made in the nineteenth century by Jacques Duban

caused some of it to be destroyed.

Chateaux de Plaisance.

It was about the beginning of the reign of Francis I that the chateau de plaisance was first established in its own right and this coincided with the acceptance of neo-classic forms that had been introduced at an earlier date.

The early chateaux de plaisance in the open country were in many cases the older chateaux remodelled or enlarged, and although no longer required to withstand a siege it was still necessary for some time to provide security against the roving bands of marauders that continued to move about the surrounding country. The fosse and pont-levis, however, sufficed for this purpose and were retained for some considerable period after the loopholes and embattled towers of the medieval period had become unnecessary.

The slightly narrower windows of the earlier chateaux were enlarged and additional windows provided to give the light and air which was now demanded. Violet le Duc suggested that openings were cut vertically in many of the feudal towers to provide large windows, one above the other with panels between. The jambs being made good by being concealed with stone thus forming the pilasters which are a familiar feature, but this can be taken as pure conjecture as no records exist to prove the truth of it.

In cases where the chateau was a wholly new building and where foundations of earlier buildings were disregarded it was generally placed on even ground and the plan tended to become symmetrical. Yet still the outline remained broken with the steep gables, chimneys and dormers that are proper to a northern climate and even the towers, turrets and other features of feudal architecture were largely retained, as at Chambord.

The French chateau was never transformed into any likeness of the Italian villa but it was nevertheless so radically changed as to lose that admirable logic of design which distinguishes the French architecture of the middle ages which was an outgrowth and expression of the requirements of that time.

26↑

26↑

An interesting example:of development is the chateau at Chenonceau.

The estate of Chenonceau, on the banks of the river Cher, was the subject of a lawsuit which lasted

some seventeen years and at its conclusion the chateau was awarded to the minister of finance, Thomas

Bohier in 1513.

The estate comprised a fortified castle of the fifteenth century including the feudal tower of Marques

built about 1432 by Jean Marques on the authorisation of Charles VII to strengthen the chain of

defences, and also a mill situated in the bed of the adjacent river.

At the onset of his possession, Bohier undertook the restoration of the castle. He pierced openings in its

walls and added dormer windows which were skilfully enriched by ornament and detail in the

Renaissance style.

Shortly afterwards Bohier modified his design. He destroyed the ancient castle with the exception of

the Tower of Marques which still stands today, and built his dwelling on the piles of the mill over the

water, Bohier, having been to the campaigns in Italy, had returned filled with admiration for its

gracious villas. The details of these he attempted to emulate without a great deal of success.

The work in constructing this small chateau de plaisance lasted from 1515 to 1522 and was undertaken

by local masons, who were without doubt not in touch with the current Italian art, because they appear

to have been content with imitating the ornamental motifs, such as the fluted pilasters which decorate

the Tower of Marques.

Flamboyant Gothic ideas still survive in the neo-classic details and the portal to the main block has the

three-centred form of arch with a keystone and continuous impost. The jambs and archivolt are in

three-planes or order of a shallow projection, with simple mouldings of a semi-flamboyant character.

There is no entablature to this portal, but a corbelled cornice supporting a heavy balcony passes over

the arch. This balcony has a curved ressaut at the ends carried on a massive corbel in graduated rings of

overhanging masonry with a compound support beneath consisting of a stout pilaster and two small

shafts. The flamboyant idea running through this nondescript scheme is shown in the depressed form

of arch and by the simulated interpenetration at the imposts of the pilasters.

The main block has a rectangular plan with a round tourelle on each corner with a conical roof.

A straight passage from the entrance cuts the pavilion in two: this passage with its Gothic vaulting

leads from the front to the galleries at the rear and on either side opens into salons. The chapel and the

library in the east were built on the projecting piers of the original mill and were connected by an open

loggia.

In 15:65 Chenonceau was confiscated by Francis I.

27↑

27↑

Contemporary with Chenonceau is the chateau of Azay le Rideau, an entirely new structure which was also built between 1516 and 1524 by Gilles Berthelot who was counsellor and secretary to Francis I. His initials and those of his wife appear in many parts of the building.

28↑

28↑

This chateau, which is of moderate dimensions, is probably the earliest instance of an attempt to make a deliberate break with the medieval style in the planning of living rooms and has a far more advanced plan than Chenonceau. It is here that there is one of the earliest examples of stairs with parallel straight flights separated by a wall.

29↑

29↑

The plan, although unusual and 'L' shaped which may possibly be due to the foundations of an earlier chateau of the medieval period, is logical and harmonious. It is quite likely that it was intended to entirely enclose the court either by a screen or curtain wall as the chemin de ronde is omitted from the re-entering facades which are more richly decorated than the outer ones. The main decorative feature being the ornamental bay of four storeys of which the dual entrance forms part and which consists of a profusion of neo-classic and flamboyant details.

30↑

30↑

The chemin de ronde is supported on corbel brackets having a superficial resemblance to the medieval machicolations of the early chateau fort and its numerous small windows are so placed as to give the intervening wall solids somewhat the appearance of merlons, while the steep roofs crowned with spiky pinnacles and high chimneys make up a total composition of great interest.

There is no pretence at defence although there is one round bastion, and at the remaining angles are tourelles simulating those of feudal times.

31↑

31↑

The walls are comparatively plain with horizontal emphasis being obtained from the moulded string courses which are at window, head and sill levels on all floors. The windows themselves are arranged one above the other in vertical lines with panels between, the whole of which bound together with classical pilasters typical of the period are symmetrically spaced.

32↑

32↑

The careful setting out of the elevations as a whole suggest that this was the work of a practised designer, producing an air of restraint and refinement. Much of the design was due to Etienne Rousseau, who came of a long line of master masons.

33↑

33↑

While Azay le Rideau was in the course of erection, Francois I selected a marshy site in the forests of Sologne for a new hunting lodge, unhampered by existing buildings.

Preparatory works were set on foot in 1519 for building the chateau of Chambord, which all but ceased during the Italian wars and the king’s captivity in Spain but building was resumed with vigour on his release in 1526, the bulk of Chambord being erected within the next ten years.

34↑

34↑

Approaching more nearly the usual type of chateau de plaisance, Chambord is an immense building planned symmetrically but preserving something of the medieval tradition. There is a central block corresponding to the old donjon, completed.about 1539, within a court surrounded by buildings, the facade of this donjon block forming the centre of the main front. The castellated idea is maintained by the, enormous round bastions which flank the angles, of the parallelogram which forms the plan.

The most remarkable feature of the centre block is its great hall planned as a Greek cross, and in the middle where the four arms meet is the famous monumental double staircase, constructed with two stairways winding round a central tower, and which discharge at each landing on opposite sides.

The four arms of the cross form four halls which are lit from the ends. The stairs are lit by a lantern on the roof and by openings between its piers.

35↑

35↑

The walls of Chambord are adorned with pilasters as at Blois. Though the design below the cornice is

much simpler, above the cornice however, it is the richest of all the great French chateaux. With its

steep roofs and manifold dormers, chimneys and the central lantern over the double staircase, it

presents an aspect which for multiplicity of soaring features resembles the late Gothic. Many of these

features are redundant - its vast chimneys, adorned with free standing orders, niches and panelled

surfaces, dormers with overlaid orders of pilasters, pediments, scrolls and an endless number of filigree

ornaments.

The combination of a riotous profusion of delicately ornamented details, each individually interesting,

with the rather clumsy general proportions, fails to produce a wholly pleasing effect.

Much of the treatment of the elevation resembles Francis I work at Blois such as the introduction of

slate panels in the stone surfaces as a decorative element.

36↑

36↑

Considerable work at Chambord was also carried out by Henri II who succeeded Francis I. He completed the eastern wing and court with its staircase tower in a somewhat similar manner to that of Francis I in the western court. His work however, omitted the slate applique and the excessive ornament and was more refined although it has the appearance of being incomplete when compared with the earlier, which is probably due to the exuberance of carving and sculpture on the latter work.

The forward halves of the wings round the southern half of the chateau were carried up no higher than the front screen building, which contains dwelling rooms, and the.front towers were never carried up to their full height and remained at the level of the balustraded terrace which covered these single storeyed buildings.

Louis XIV, who carried out extensive alterations, replaced these balustraded terraces by mansard roofs, but they were included in the considerable portions which were much damaged during the Revolution. However, restoration which has been undergoing since 1830 has replaced much of the damaged work.

Extensive renovations were being carried out during the visit of the writer at the end of 1949.

One of the main characteristics of Francis I architecture is the combination of panelled or fluted pilasters with a window divided by a stone mullion and transome after the late Gothic manner, and although they are derived from different types of architecture the two features blend to form a definitely marked and fairly consistent style. Generally the window opening fills most of the space between the pilasters, and sometimes the pilasters are coupled. Although there are other variations, this is the most common.

37↑

37↑

Valencay, a chateau of typically Francis I style, was commenced in 1540 by Jacques d'Etampes who built the North wing. Bearing little or no trace of the more mature Renaissance manner it is unlike the usual work of de l'Orme to whom it has been attributed. It is also likely that Jean de Lespine was responsible for some of the design in view of the similarity of certain features to his known works elsewhere in the Loire valley.

38↑

38↑

The plan, which was never completed, although somewhat unusual, reproduces on a rather grander

scale that of the neighbouring chateau of Veuil which was built by an uncle of d'Etampes. The entrance is placed in the main building which thus forms the front of the court instead of the back, while the screen or rather the balustraded terrace which does duty for it, divides the court from the garden. The court is, however, normal for the period in other respects, and was to have been enclosed between three ranges of buildings at right angles with the cylindrical towers at the external angles.

39↑

39↑

This at least looks as if it had been the intention, but the wing at the left of the court is lacking and the right wing was so much enlarged in the seventeenth century that it became the most important part of the building and usurped the place of the central block. The balustrade which takes the place of the screen, many of the dormers and probably the domical roofs of the towers are also of this period. But thoroughly in the character of earlier works is the massive and stately pavilion, a clear reminiscence of the medieval donjon which occupies the central position, in the same way as the donjon at Chambord. At the extremities of this wing rise two round towers. In the western one, the disposition of the pilasters and the design of their capitals appear to be an imitation of Chambord and some other features resemble details from Chenonceau.

The unusual dome roofing the towers, and the placing of the orders, and some features in the donjon block, although new to the locality, are simple manifestations of the new style following the arrival of Serlio, the Italian at the French court.

The western wing at right angles to that of the sixteenth century work, was constructed between 1640 and 1650 by Dominique d'Etampes, a great-grandson of Jacques. Of this latter work, little remains intact except a portion adjacent to the 'new tower' and which is decorated by Ionic pilasters in two storeys.

A century later, about 1775, a new owner, de Villemorien added the 'new tower' to match the existing building, and carried out considerable alterations adding a new mansard roof and substituting a single colossal Ionic order for the original two Ionic pilasters. The cornice of this portion is surmounted by an attic storey with pedimented dormers alternating with bull's eyes and stone urns, the central feature being a large cartouche forming the surround to a clock.

A less attractive chateau, but of some interest as it also incorporates more than one style of architecture is Le Lude.

40↑

40↑

Originally a feudal chateau fort it was bought by Jean Daillon in 1457, who became a minister of Louis

XI, and remained in his family for many years.

It was a 'U' shaped chateau fort with seven towers and a deep moat on three sides, while the east wing

overlooked a terrace falling down to the river.

41↑

41↑

As it stands today the chateau has the typical ground plan of three wings with a tower at each angle all enclosing a cour d' honneur, which on the west is closed by an arcaded portico.

The three wings are of different periods. That to the North was built at the end of the fifteenth century, possibly by Jean Gendrot, master mason, in the style of Louis XII and has two storeys above an arcade, the roof is carried on machicolations and has dormer gables crocketted in the flamboyant style.

42↑

42↑

The south wing of Francis I, built by Jacques de Dillon, is typical of the Renaissance with its

medallions and bands of carving, and consists of several storeys and an attic with tall gabled dormers. The east wing, also begun by Jacques de Dillon, was restored In the eighteenth century and is now a mixture of the styles of Louis XIV and Louis XVI and is completely out of harmony with the other two wings which it connects.

43↑

43↑

During the reign of Henri II, that is from 1547 to 1549, there was a drift towards regularity and

symmetry which was marked by further departures from the medieval tradition.

Round towers became the exception and square pavilions the rule. The plan that had evolved during

the previous two reigns was more generally adopted and its buildings, disposed around a rectangular

court, may be classified as main blocks, gallery wings and pavilions.

Usually all these buildings had a basement storey. Main blocks which seldom occurred on more than

three sides of the chateau had two principal storeys above this and one in the roof. The gallery wings

had one principal storey and often a flat roof. The square pavilions which had usurped round towers

were often at the angles and sometimes in the centre of a block and projecting beyond the general line

of the buildings and higher than adjoining buildings by at least a storey.

44↑

44↑

Principal apartments were in the main blocks and the pavilions. Generally entrances were adjacent to

staircases which were seldom spiral and often placed in projecting blocks. The principal one was

opposite the entrance to the court and placed in an open gallery.

Closed galleries occupied various positions in the plan usually on the inner side of the courts.

Subsidiary courts like the cour d'honneur were rectangular and were preceded by a forecourt with its

own gate pavilion not always opposite the inner one.

Other courts were often added with lower or less splendid buildings than the central one.

It was about 1547, when Henri II presented the chateau of Chenonceau to Diane de Poitiers, his

mistress, who arranged with Philibert de l'Orme for the design of a bridge of five arches across the

river Cher joining the chateau with the opposite bank.

This work, said to have been constructed by Jean Bullant, master mason, lasted from 1556 to 1559, about which time Henri II died and his widow Catherine de Medici forced Diane to exchange Chenonceau for Chaumont.

45↑

45↑

About twenty years later, under the direction of Catherine, an obscure architect, Denis Courtin, built on this bridge the famous galleries, often falsely attributed to de l'Orme. There are two storeys built in a classical style the interiors of which were decorated by Italian artists. (This part of the building was damaged in 1940).

The galleries, which were originally designed by de l'Orme to be of one storey, do tend to overwhelm by their mass the earlier building by Bohier. Much of the effect results from the contrast of the arches of the bridge with the fenestration over.

It was intended to build a block similar to Bohier's at the end of the galleries on the opposite bank of

the Cher but this work was never carried out. It is also likely that de 1'Orme was employed by Catherine de Medici to plan further extensions to Chenonceau. This scheme was to flank the main block, Bohier's pavilion, by two rectangular blocks rising also out of the river, while in front on the bank a splendid cour d'honneur was planned with a hemi-cycle at each side leading to farther buildings and approached through a great forecourt with converging sides. The whole scheme would have made the original chateau an insignificant detail by its vastness, which easily illustrates the ample conceptions of the time.

46↑

46↑

After the galleries were built no major works were carried out and the chateau passed successively into the hands of Louise, wife of Henri III, the house of Vendome and the Bourbon Condé family. It came into the possession of Claud Dupin and in 1864 suffered under the hands of Louise Pelaise who executed extensive restorations.

Sketches made by Victor Petit in 1860, show sculptured figures or caryatids on the mullions to the

main windows on either side of the portal to Bohier's pavilion, embellishments which have been

attributed to Catherine de Medici. The pilasters forming the jambs to these windows have a form of

corinthianesque capital and a string course forms the head of the windows. In addition, there were two

busts on console brackets either side of the central window over the doorway. It may be that the

chateau was like this before restoration by Mme. Pelaise took place or that the embellishments have

since been removed by a later owner more keen on retaining the chateaux in its original state.

Restoration of the war damaged portions of the chateau were being undertaken during the latter end of

1949.

As previously mentioned, when Henri II died his widow Catherine offered the choice of Chaumont to

Diane de Poitiers for the forfeiture of Chenonceau which had been one of Henri’s gifts to Diane.

In 1560, Diane built the chemin de ronde with its carved figures and emblems. The walls of this

portion are pierced with large windows to the level of the counterscarp, and sunk in square panels that

form a sculptured band round the towers at a lower level are entwined the 'C’s of Charles of Amboise,

brother of Georges for whom the chateau was built, alternating with other panels carved with the

symbol of Chaumont, a flaming volcano. Above this, on the left tower is carved the Cardinal’s hat of

Georges d'Amboise and opposite is his coat of arms. The initials of Louis and Anne occupy the central

position over the entrance with its bascule. The emblem of Louis XII, the porcupine, is sculptured on

the inside of the wing forming the entrance towers.

Originally the chateau was built as a complete quadrilateral but in the eighteenth century the North

wing was demolished, which had the effect of converting the cour d'honneur into a terrace with a view

of the valley. Thus it now has only three wings. The west wing now holds the private apartments and

the wing opposite contains the historic rooms.

Connecting these two wings is a third with a cloistered arcade.

A spiral stairway connects the entrance storey with the salle de garde on the first floor above and the

adjacent council chamber. Next to this is Catherine de Medici's bedchamber from which is a door

giving access to the gallery of the chapel. This chapel is in the form of a Greek cross and with the

windows in the Flamboyant style. The queen's astrologer stayed at Chaumont and a small staircase

leads from his room to the observatory in the tower above. Also on the first floor is the bedchamber of

Diane de Poitiers which is built in the thickness of one of the entrance towers.

During the reign of Henri IV, that is from 1589 to 1610, the plan of the chateau underwent little, or no

appreciable changes. Society had grown less refined and the arrangements of the sixteenth century

sufficed for its needs.

The fortified aspect of the chateau tended to disappear completely, although the system of projecting

pavilions in the main wings continued in use.

Previously the moat had contained water but now was often dry. The court had lost its significance and

was now sometimes represented by a mere wall or balustraded enclosure.

The division into a number of small suites of rooms was maintained and the main or state staircase

placed in the centre of the main block prevented the possibility of an uninterrupted suite of reception

rooms,

The effect of a more settled government under Louis XIII was the growth of refinement in the habits of

society. One manifestation of this was the demand for greater privacy and comfort which resulted in

several changes in the planning of chateaux.

Elegant apartments of moderate dimensions in suites approached from a vestibule and no longer

divided by the main staircase were generally desired. To ensure better lighting windows accordingly

were increased in size and generally reached from floor to ceiling. The stone mullions of earlier

periods were generally abandoned.

Although there was now a distinction between private and reception rooms there was still little

specialisation in the uses to which the various rooms were to be put.

When Gaston, brother of Louis XIII became Duke of Orleans in 1627, he returned to Blois to rebuild

the chateau in accordance the ideas of his age and in the new and now perfected style of the

Renaissance.

He engaged Francois Mansart in 1635 to prepare designs for an elaborate scheme of conversion and

additions. It was intended to demolish the buildings of Louis XII and Francis I with the famous

staircase, but this work was never carried out.

47↑

47↑

Only the west side of the chateau was rebuilt, that of the west end of the Francis I wing with the Stag

gallery and almost all the Charles d'Orleans work and the ante chapel.

Insufficient funds prevented building more than the block at the back of the inner court. This building

is in its way a masterpiece of design; although lacking harmony with the neighbouring wings it is

simple and yet elegant.

48↑

48↑

In this wing there are no balustrades and also no divisions between the blocks and no break in the

entablature to disturb the quiet simplicity of the mansard roofs. In the middle only, is there a break, and

this in the entrance with its columns and pediment. The curved colonnade leads by quadrants to this

entrance while the central bay is emphasised by the semicircular pediment enclosing a cartouche and

buttressed by trophies. The use of the colossal order so often adopted at this period was avoided..

The back of this building is equally severe and dignified, and gains strength from the retaining walls

below. Both at the front and the back the high roof unbroken by dormers, gives the impression of

dignity. The height of the storeys, breadth of spacing, boldness of masses and general proportions

require no rustication to convey the feeling of repose.

In 1660 after Gaston died, Blois ceased to be a royal residence and fell into decay.

Towards the end of the reign of Louis XIII there was a great .development in domestic architecture.

The plan shows further steps towards compactness and comfort with still greater specialisation of

rooms. Previously it was the practise to plan one room deep with windows on both sides. Now it

becomes usual to make them two rooms deep with light on one side only.

The salon is now the equivalent of the medieval hall and occupies the position recently held by the

grand staircase in the main axis. The salon, often two storeys in height and elliptical in plan, forms the

entrance hall to two suites - one on either side.

Windows become very large, but large dormers of earlier times give way to small ones or continuous

attic fenestration.

The elevations indicate a tendency to decorative pomp with increased scale in many cases and much

sculpture. Detail is simplified and more refined with less clutter.

There were very few changes in the Louis XIV period and although there is not as much rustication;

the massiveness of the Louis XIII style is still retained.

There is a surprising similarity between most chateaux of this period, the difference mainly being in

the treatment of the central feature.

Generally, there is a drift towards pure classicism, but the aim was at group effects in classical detail

and symmetry rather than a single clearly expressed idea.

The style of building resulting from the national reorganisation of Henri IV was the sober and

economical common sense architecture in which classical elements are latent rather than expressed and

with much use of brickwork and stone. The buildings of this period are characterised by a certain

excess of massiveness in their proportion which is enhanced by the frequent use of the square dome

and the mansard roof.

These characteristics, combined with profuse rustication, are well shown in the chateau of Cheverny

commenced about 1634.

49↑

49↑

The building consists of three pavilions in a single large but compact block. The central pavilion is too narrow for its important position in addition to being only of medium height. The pavilions on each side of this, however, on the contrary are enormous and their importance is increased by the quadrangular domes which form their roofs. The latter appear to be too wide in relation to the connecting blocks.

Its long white garden front has a certain awkward charm of its own even if it is singularly inapt in its proportions.

The rear front shows the system of stone quoins, typical of the period, employed to connect the windows in vertical lines instead of the pilasters of an earlier day and the substitution of windows with wooden frames and casements for stone mullions with leaded lights, which became general about this time.

The interior of Cheverny retains for the part its decoration of the seventeenth century and, in addition, an example of parallel flight stairs with carved stone balusters, carved piers and spandrels instead of a wall as at Azay le Rideau.

About 1650 the financier, Guillaume Charron constructed the centre block of the chateau of Menars in the contemporary style.

50↑

50↑

This work faced with rough cast, has dressings of stone to the windows and stone quoins. The roof of

slate was continuous over the whole, including the slightly projecting pavilions at the ends, and was

only broken by a row of pedimented dormers.

Towards the end of the century a nephew of the financier did much to improve the entourage by

creating terraced gardens overlooking the Loire and a canal.

In 1760, Madame Pompadour acquired Menars and she entrusted Ange Jacques Gabriel in 1763 with

the construction of two additional wings to the ends of the chateau, to conform with the style of the

earlier work. The whole of which still stands today.

The changes in planning and decoration were many during the Louis XV period from 1715 to 1774.

The vast imposing halls persisting in the previous century no longer served the needs of society. The

congenial atmosphere required for intimate gatherings resulted in the large apartments being broken up

into suites of small ones.

At this time greater preference was being given to the building of smaller chateaux and in fact most of

those erected can hardly be little more than country houses.

The earlier half of the period was not so productive as the later and consisted mostly of alterations and

the redecoration of earlier chateaux.

Architects and master masons.

In all the preceding paragraphs little mention has been made of the professional architect. The man specifically trained as a designer and with an expert knowledge of building methods was unknown, and it was not until about the sixteenth century and as the result of increasing familiarity with Italian design, that the need of such a person was realised by the nobles.

The person up to this time responsible for the design was usually a master mason and he generally

supervised the construction and very often took a practical hand in the work whenever necessary. The actual authorship of the principal buildings of these earlier periods has been the subject of much controversy, and the arguments of those who attribute it almost exclusively to Italian designers are not convincing. This argument suggests that the French master mason was incapable of producing the work of the Renaissance. However, it was the same master mason who was producing the masterpieces of Gothic architecture which were being built at the same period and which illustrate admirably the fluency of their work in the indigenous style and their uncertainty in the Italian vocabulary of ornamentation.

One can assume that in actual fact the French master mason or builder, who was later to become the architect, was the person who designed the building in its mass, while it is possible the Italian craftsmen were the ones responsible for the embellishment of the individual parts of the building.

One of the early designers, Jehan Regnard was a Master of the King's works from 1473 to 1491, and to him have been attributed many of the oldest parts of the chateau of Amboise. Many master masons were employed at Amboise under Charles VIII, Louis XII and Francis I, including Colin Biart, who also worked at Blois, Roland Leroux, Louis Amangeart, Guillaume Senault, the brothers Francois and Jacques Sourdeau.

The Italian architect, Fra Giovanni, who was in the party brought back from Italy by Charles VIII, worked at Amboise along with Dominique da Cortone, also called Boccador. Boccador, in addition did much work at Blois and Chambord.

One of a family of master masons, Pierre Valance carried out works at Blois including some of the

Francis I wing. Trinqueau or Pierre Nepveu, was responsible for work at Chambord and Chenonceau. On the former chateau he worked in conjunction with Denis Sourdeau. When Sourdeau died in 1534 he was succeeded by his brother in law, Jacques Cocqueau who eventually took sole charge when Nepveu died in 1538.

Following their association with the Italian architects these French master masons, who came of families that had been for generations associated with the actual construction and decoration of buildings from a practical point of view, gradually began to concentrate on the design and supervision, and eventually became architects. One of these who made a lasting impression on French architecture of the sixteenth century was Philibert de L'Orme, whose work at Chenonceau has been referred to.

The most famous of French architects, however, to work on the Loire chateaux was Francois Mansart, previously mentioned in connection with his work at Blois and Chambord. His work illustrates well the later Classical period of French Renaissance, with the free use of classical orders resulting in a dignified style of architecture, but nevertheless without the interest of the earlier periods.

Conclusion

The survey of the chateaux illustrates quite clearly their historical and architectural development, and

commencing with the early feudal chateaux one can easily follow the continual transition of style. The great change in ideas and ideals., which after the remarkable intellectual and artistic life of the late Gothic, which was manifested in the so-called Renaissance, is not always correctly conceived.

The character and merits of the fine arts of the Renaissance, as compared with those of medieval times, have not often been set forth in an entirely true light. Of the merits of the best neo-classic art of the sixteenth century there can be no question, but the belief that this art is superior in its entirety to that of the Gothic will not bear examination in the light of impartial comparison.

On the north of the Alps, the Renaissance had not the same meaning that it had in Italy, and in France, where its influence was first felt, this art naturally assumed a different character. The term Renaissance is in fact not properly applicable, for the French had not had a classic past, and the adoption of architectural forms derived from Classic antiquity was not at all natural to them.

Through the course of development, the French master masons had acquired and perfected a peculiar genius which had found expression in forms of art that were radically different from those of ancient times, and in departing from the Principles of this native art, they violated their own traditions and ideals which had been free, unconventional and intelligible to the people.

It has often been suggested that French architecture was only superficially affected by the Renaissance influence and its essential character survived beneath the classical embellishments. This, however, is not the truth, as classicism did effect a fundamental change in this architecture by giving it an artificial instead of a natural character: but despite one’s feelings concerning the particular style, without a doubt, it was the early attempts at the neo-classic forms of expression in the Loire valley which were the forerunners of the perfected examples of Renaissance elsewhere in northern Europe.

| Bibliography | |

| N. Pevsner: | An Outline of European Architecture. |

| Francois Gebalin: | Les Chateaux de la Loire. |

| T. Cooke: | Twenty-five Great Houses of France. |

| Old Touraine. | |

| Victor Petit: | Chateaux de la vallee de la Loire. |

| R. Blomfield: | History of French Architecture. I |

| C. Moore: | Character of Renaissance Architecture. |

| J.A.R. Marriott: | Short History of France. |

| R. Feddon: | Crusader Castles. |

| S. Toy: | Castles. |

| W.H. Ward: | Architecture of the Renaissance in France. |

| French Chateaux and Gardens in the XVIth cent. | |

| E. de Granay: | Le Chateau de Chambord. |

| C. Ferdinand: | Chateaux de France. |

Articles published in Architectural Review and various other publications.